Seaside Entrepreneur: Victor William Durrant (1875-1947)

Victor was born on October 9th, 1875 in Kessingland, Suffolk, UK, a market town located almost five miles south of Lowestoft and bordered by the North Sea. Victor was the second son and one of fifteen children born to parents George Durrant, a fisherman, and his wife, Elizabeth Ramsey Tripp.

Victor William Durrant’s Birth Record

Almost two years later, in the summer of 1877, Victor and his younger brother Colls are baptised in St Edmund’s Church. William Woodward, the rector, bent over the enormous ornamental 15th-century font [1,2], wet their heads and that of four other children that Sunday.

Victor William Durrant’s Baptism Record

By 1881, it appears Victor’s father is on an upward trajectory. Now working as a fish merchant, George and the family are living on Beach Road in Kessingland, close to the sea and next door to their extended family.

1881 Census [3]

William Daniel Durrant, Victor’s uncle, is a boat owner and may have worked with his brother, George. Victor, his siblings, and cousins likely attended nearby Lower School [4] on Church Road. No doubt the group of children would have played along the windswept Kessingland beach, running along the sandy hills and splashing around in the chilly water on warm summer afternoons.

Beach Road in Kessingland, c.1900 [5]

Ten years later, the family relocate to Lowestoft. George is still working as a fish merchant, but he is also managing The Brewer’s Arms, a pub on Belvedere Road close to Lowestoft harbour.

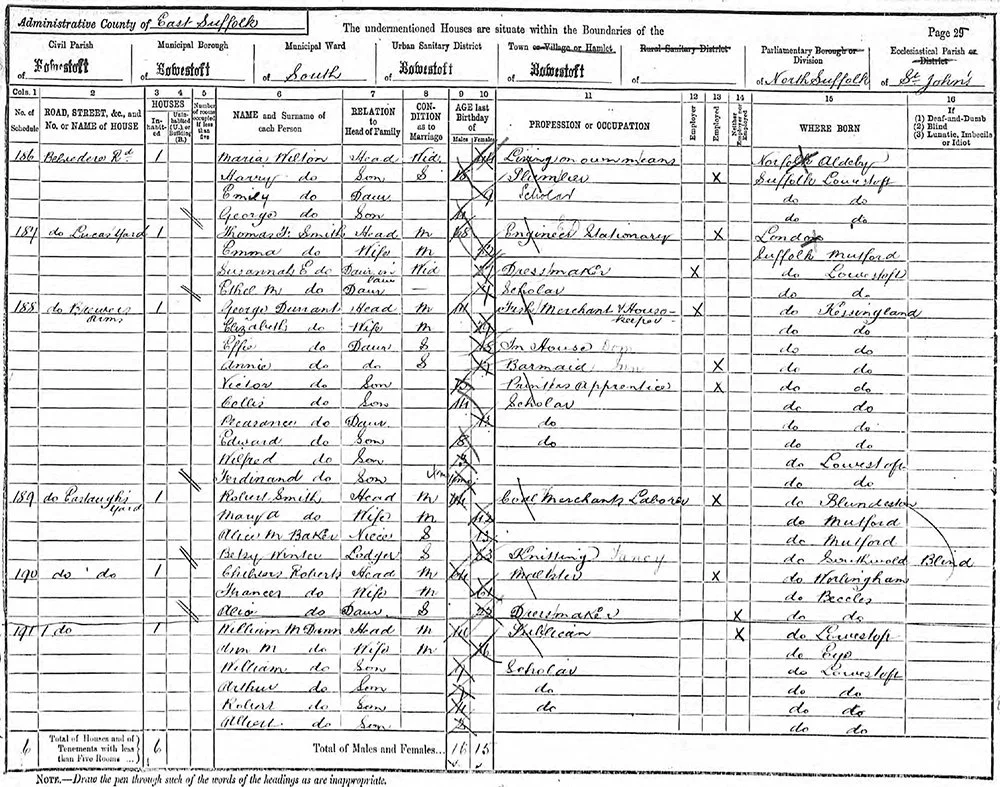

1891 Census [6]

While Victor’s sister Annie is supporting the business by working as a barmaid, Victor is striking out on his own. Victor has secured a job as a printer’s apprentice and seems to be steering away from the traditional fishing-related roles that his family had relied on for generations. However, this career choice was short-lived and in 1894, at the age of 19, Victor enlisted in the Royal Navy [7]. It remains unclear what drove this change in his ambitions. Perhaps Victor was searching for adventure and an opportunity to see the world, spurred on by stories like ‘The Good Ship Mohock’ written by author William Clark Russell, a prolific writer of nautical novels. The story first appeared in the Lowestoft Journal in July 1894 [8] and was described by reviewers as enjoyed by “those who love ships and sailors and the sea [9].” Perhaps Victor is inspired by the extensive propagation of British Navalist sentiment that was pervasive during the second half of the 19th century. The Naval Defence Act, signed by Lord Salisbury in 1889, committed significant investment to growing British naval superiority. The government made over £20M available for fleet expansion along with requisite recruitment and initiatives like ‘hurrah trips’ saw naval ships cruising along the British coast, stopping at ports to recruit from local populations [10].

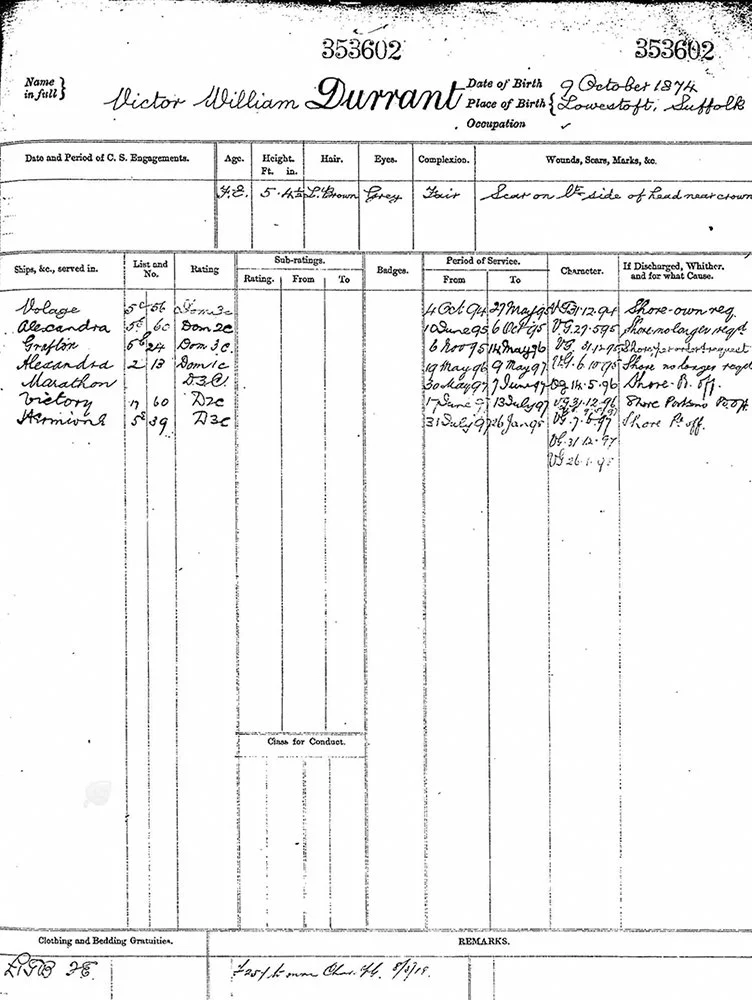

Naval Service Record for Victor William Durrant [7]

Victor is relatively short in stature by today’s standards, standing at 5ft 4½ inches when he joins the Navy. He had light brown hair, grey eyes, and a fair complexion. He appears to be in good health barring a scar on the left side of his head near his crown.

On October 4th, 1894, Victor joins the Volage, an iron screw corvette training ship that is part of the training squadron [11]. Changes in service numbers in 1894 [12] indicate that Victor was assigned to the service branch associated with Officer’s Stewards, Officer’s Cooks, and Boy Servants. Victor begins his naval career as a Domestic 3rd Class and within seven months is promoted, working as a Domestic 2nd Class on HMS Alexandra.

HMS Volage at sea [13]

HMS Alexandra was an ironclad battleship, rigged for both sail and steam power, and the fastest warship at the time [14]. In 1891, the vessel became the flagship of the Admiral Superintendent of Naval Reserves at Portsmouth, so it is likely that Victor’s first experience of visiting Portsmouth would have been in 1895.

HMS Alexandra [14]

Shortly after Victor joined the ship in July 1895, HMS Alexandra was with the Reserve Fleet at Torquay preparing for manoeuvres around Lough Swilley on the northwest coast of County Donegal [15]. It had been a struggle to assemble the fleet, given the bad weather, but exercises were underway by the end of the month.

Victor’s responsibilities during the manoeuvres are unclear, but he would have been involved in the exercise:

“The first proceeding is to clear away and load the guns and place them in the cease-firing position. Mess tables, stools, and other gear are cleared out of the batteries, water-tight doors not required open in action are closed, the magazines and shell-rooms are opened, the electric light switched on, and all made ready for rapidly passing the ammunition up to the guns. Stretcher parties get into place near the guns for carrying away the wounded, and rig the tackle by which they are lowered down to the deck below the water line, where the surgeons and their assistants are rapidly preparing for their work. Pipes and hoses for fire extinction are got into place, and when everything is ready each officer reports to the conning tower, by voice tube, that his quarters are cleared and prepared for action. When every part of the ship is reported ready, the “wheel” is sounded, and the men seize their small arms, place them in racks provided near their stations, and put on their belts and pouches…When “boarders” is sounded, those men whose guns are not engaged fall in on the quarter deck by gun’s crews, armed with their rifles, the marines in rear in single rank. If the call of boarders is followed by the bugle advance, some of the men leave their rifles, and arm themselves with cutlasses from racks placed on the quarter deck…A layman, watching the rushing hither and thither of bodies of men scrambling up and down gangway-ladders, and the general haste and hurry below and above, would think the scene was one of indescribable confusion: but such impression would be the exact reverse of what is really the case. Each man and boy knows his station and exactly what to do when he gets there [16].”

A month later there were false reports that the Alexandra had been in a collision with another ship in Bantry Bay, which undoubtedly would have caused anxiety among Victor’s family:

“The news spread rapidly, a great deal of alarm and consternation was caused, and for some time it was difficult to convince persons who had friends on board that there was not the slightest truth in the report [17].”

The reality was that accidents did happen. Rough seas and high winds often caused problems and occasionally led to fatalities. That same month, several lives were lost in boating disasters, including that of Daniel Green from the HMS Alexandra [18].

Towards the end of the year, Victor was assigned a new ship and joined HMS Grafton shortly after the ship was commissioned in Portsmouth. Victor and the crew sailed for China on November 11th, 1895 [19], destined to deliver relief crews to the China station. In little more than a week, the ship was experiencing problems. On arrival in Gibraltar, the Grafton was beset by engine issues [20], but with defects resolved the crew sailed onward to Singapore, reaching port by December 21st [21]. The Grafton arrived in Hong Kong on December 29th [22] and so Victor experienced Christmas Day at sea with his fellow crew mates.

Entrance to Hong Kong Port c. 1895 [23]

Bubonic plague was rife in Hong Kong in the 1880s and 1890s, consequently, the crew of HMS Grafton may have experienced restricted shore side visits. It’s possible Victor’s only view of the exciting and vibrant Asian culture was watching the crimson-masted junk ships sailing around the harbour.

With crew exchanged, the Grafton sets sail for England on January 8th, 1896 [24] sailing to Singapore, then through the Suez Canal to Port Said in Egypt and onto Malta [25] before arriving in Portsmouth on February 16th [26].

The sailors of the Grafton made their way to Malta in March and were heading back to Gibraltar after collecting crew from HMS Collingwood when they needed to respond to a sinking vessel in the Mediterranean Sea. The German steamer, Neapal, had quickly taken on water after striking the Galita Rocks off the North African coast and required immediate assistance. With the Neapal crew onboard, the Grafton headed back to Plymouth and then sailed onward to Portsmouth [28].

In May 1896, Victor rejoins HMS Alexandra following another promotion to Domestic First-Class working as either a Steward or Cook. During the next 12 months, the ship remains in UK waters. For the time being, Victor’s international travels are over.

Following a brief period on the Marathon serving under Acting Commander Henry H. Bruce [29], Victor is reassigned to HMS Victory, and for unknown reasons is downgraded to a Domestic 2nd Class despite consistently receiving a character assessment of ‘Very Good. It is almost certain that Victor served on Nelson’s famous flagship from the Battle of Trafalgar. At the time, the ship was anchored on the Gosport side of Portsmouth harbour, training sailors as a Naval Signal School [30]. Consequently, Victor is in Portsmouth on June 26th, 1897, and present for the Diamond Jubilee Review of the Fleet at Spithead. The Naval Review of 1897 was reported: “as the greatest display of Naval power that was ever made in the history of the world [31].” Over 160 British naval ships lined up between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight to mark Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee–60 years on the throne. The Review was reportedly a magnificent success with beautiful weather and unparalleled visitor numbers lining Southsea Beach, Stokes Bay, and the shores of the Isle of Wight [31].

Gosport side of Portsmouth harbour. HMS Victory moored nearest to shore (top right) c. 1900 [32]

Victor may have met his future wife, Maria Efford Kate Hilker, around this time period, maybe even during the Jubilee celebrations.

Victor’s final deployment was on the Hermione as part of the Channel Squadron. This saw him sail around the Mediterranean, from Gibraltar around the Spanish coastline to the Balearic Islands [33-36]. He arrived back in Plymouth on December 14th after departing from Ria de Arousa [37], an estuarine inlet on Galicia’s Atlantic coast.

Victor’s travels officially come to an end on January 26th, 1898, after a relatively short naval career of little more than three years. Still, it was an experience that changed his life forever. Not only did it provide him with the skills he would rely on in civilian life, but it also gave him a connection to Portsmouth, which became his home.

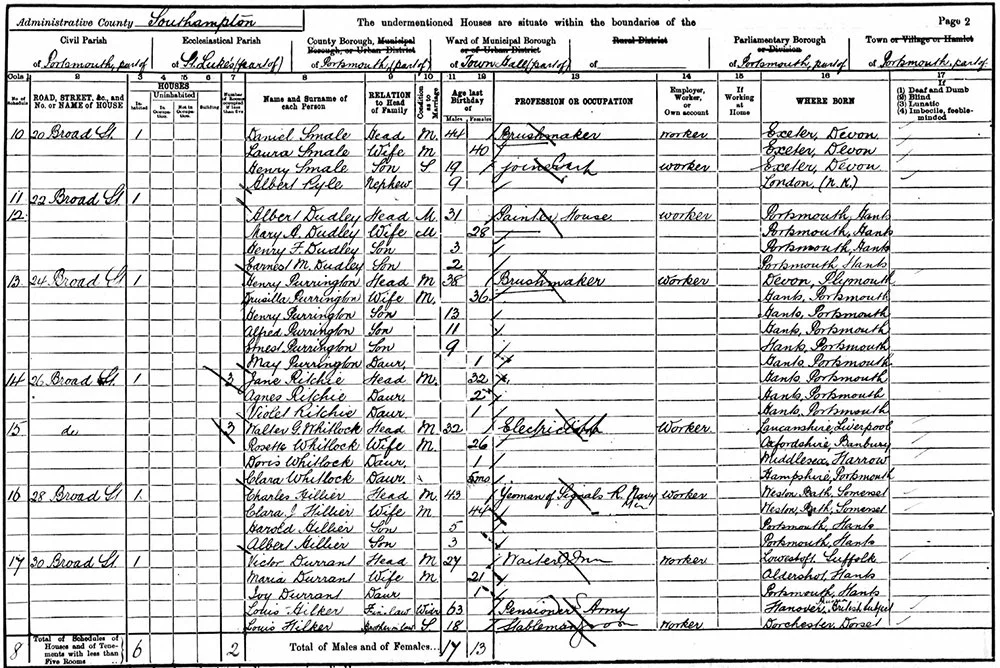

Victor begins renting a property on Broad Street in Somerstown, Portsmouth on October 14th, 1900 [38]. At the time of the 1901 Census, Victor is head of the family. Maria is now living with him as his wife and they have a young daughter, Ivy Dorothea Victoria. Maria’s father, Louis Hilker Senior (an army pensioner), and her younger siblings, Louis Hilker Junior (a stable man), and her sister, Dorothea (a cigarette-making apprentice) all live with the young couple.

1901 Census [39]

The responsibility of looking after the family must have been quite intense for Victor. There is no guarantee that working in the hospitality industry as a waiter would have provided a significant income and he may have been reliant on generous tips from customers to look after his growing family.

Sometime in 1902, Victor and Maria welcome their second daughter, Hilda Florence Constance. Their third daughter, Doris Gladys, quickly follows in 1903. This may have prompted their subsequent move to 21 Gold Street in Southsea a year later [40].

Their first son and fourth child, Edward Louis Victor, is born in early 1905. That same year, the family move again. This time to 85 St Vincent Street [41].

Early 20th-century map of Portsmouth. Home locations for the Durrant family depicted with red circles [42]

The property was in an increasingly more attractive area and so the rental value increased [43]. It’s possible that the family was living beyond their means and needed ways to reduce their living costs. At some point, Victor rents a room to Annie Louisa Payne, who then proceeds to steal some soft furnishings. The case is reported in the Evening News [44]:

“Annie Louisa Payne, 33, was charged with stealing a sheet, valued at 3s, the property of Victor William Durrant. of 85, St. Vincent Street. It appears that on the 2nd inst. The prisoner took furnished apartments at the prosecutor’s house, and at that time the sheet produced was then on the bed in her room. On the 8th inst. The prisoner left the house, saying that she was going back to work, but she did not again return. The prosecutor at once gave information to the police. Evidence was given as to the prisoner pawning the sheet and giving the ticket to a friend, who handed it to Detective Hoare. The prisoner, in mitigation, pleaded that she stole the sheet in order to obtain food. The Bench, on obtaining a promise that the prisoner would go to the Workhouse, decided to deal leniently with her, and bound her over for three months.”

Despite living together for a number of years, having several children, and sharing a last name, Victor and Maria had not been married. This all changed on January 2nd, 1907. The couple was married by certificate at the Register office in Alverstoke.

Marriage Certificate for Victor Durrant and Maria Hilker [45]

At this point, Victor is still employed as a hotel waiter. While his father, George, is listed on the certificate, it is unlikely that his family from Kessingland had made the journey to witness their union. The witnesses have no clear link to either Victor or Maria and certainly aren’t family members. The couple’s residence is also listed as Trinity View in Gosport, some distance from Portsmouth, which raises further suspicion. The most likely scenario is one that looks to avoid any hint of impropriety. Victor and Maria probably travelled from Portsmouth as foot passengers, using the Gosport ferry to travel across the harbour to get married.

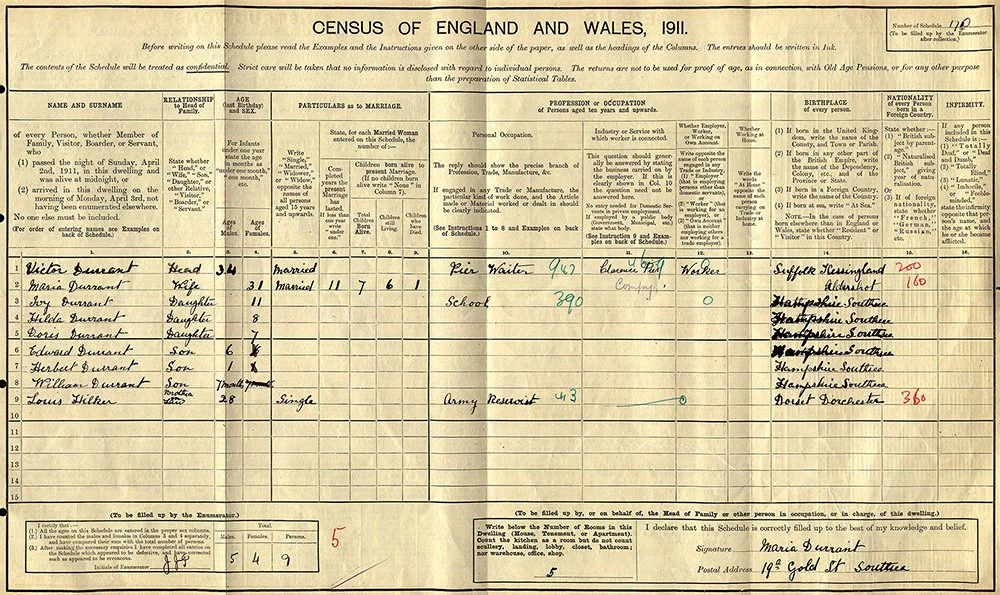

Between 1907 and 1908, the family moves again, this time returning to Gold Street (19a – Arundel House apartments) [46]. Maria falls pregnant again. She gives birth to Herbert George in 1909 and William Arthur in 1910. At the time of the 1911 census, the couple have been together for over a decade and had six healthy children. However, like many others, they have also experienced loss with the death of one of their children (name and circumstances currently unknown).

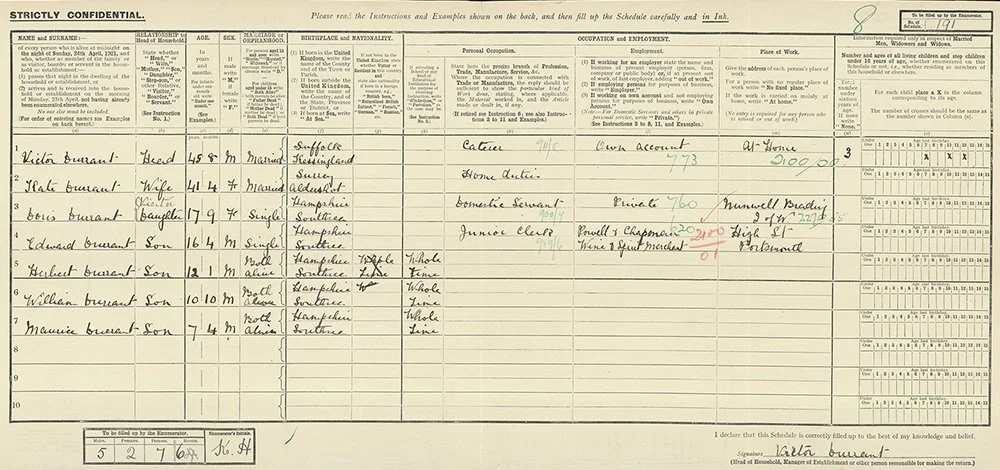

1911 Census [47]

The Victorian and early Edwardian years saw the widespread expansion of English seaside resorts across the UK. Southsea was one of many places that drew enormous crowds of visitors to its promenades and beaches, making it a popular holiday destination. The tourist industry was booming, and Victor took advantage of the many associated employment opportunities. In 1911, he is working as a waiter at Clarence Pier.

Clarence Pier opened to the public in 1861. The elegant octagonal pavilion was added twenty-one years later, and the pier was further extended in 1905 to accommodate increasing boat traffic, making excursions to the Isle of Wight [48]. There would certainly be plenty of holiday-makers to keep Victor busy.

Postcard of Clarence Pier, Southsea c. 1915 [49]

On February 9th, 1914 Maria gives birth to their final child, Maurice Gordon. The family’s joy would be short-lived with tensions rising in Europe. Britain joins the conflict on August 4th, 1914.

The need for vast amount of recruits was recognised early on. With mounting casualties on the front, the government had no choice but to increase numbers by conscription. In 1916 the Military Service Act was passed extending conscription to married men up to the age of 41 [50]. In 1917 Victor is referred to a military service tribunal. He is now working as a Refreshment Room Manager for Portsmouth United Breweries Ltd. The tribunal grants him an exemption since he is too old for military duty. However, presumably, Victor feels compelled to join the war.

Exemption Register for Portsmouth. Judgement of Hampshire Military Tribunal [51]

His medal card indicates he served as a private in the Army Service Corps (ASC) as part of the mechanised transport division and earned the Victory and British Medals for his service overseas [52]. As part of the ASC, Victor would have played an important logistical role. Perhaps he was part of the ammunition columns that delivered heavy artillery to the front lines, maybe he handled bridging and pontoon units, or perhaps he drove a motor ambulance that transported medical supplies and wounded soldiers [53].

Army Service Corp convoy transporting troops in World War One [54]

After the war, Victor returns home to his family and strikes out on his own. In 1921 he appears to be running a catering business from his home in Gold Street [55]. At the time of the census, he is living with his wife Kate (Maria) and their four youngest sons. Their daughter Doris is visiting from the Isle of Wight.

1921 Census [55]

A year later he is running a Ham and Beef shop from premises in Osbourne Road (Number 36) [56], sharing the same address as L&A Macey, costumers (Paris house). This appears to be temporary as he begins managing a cafe on Clarence Esplanade on behalf of the Southsea Beach and Publicity Committee in 1923 [57].

Victor shows leadership in May 1924, representing the views of stall holders on Clarence Esplanade at a Police Court hearing. Patrick O’Brien, a travelling showman, applied for a music licence for his fair but local views were clear, describing the fair as “noisy” and “unsanitary”, bringing a “rough element” while encouraging “immorality” and arousing “unclean passions” [58]. Victor was more pragmatic and stood in front of the magistrates stating “that as soon as the music started on the fairground, large crowds were drawn from the Esplanade and towards hawkers.” The licence was not granted.

On April 24th, 1926 the London Gazette announces the creation of two cities, Portsmouth and Salford [59]. Vast expansion, rapid population growth, and a long campaign by the borough council had secured Portsmouth’s elevated status. Living in Portsmouth, with its vibrant seaside community, is a world away from Victor’s childhood home in the small fishing village of Kessingland.

Victor was compelled to place an advert offering a reward in the local newspaper in July 1926. It was windy and raining heavily [60] when he lost a bundle of stamps on the corner of Cecil Grove and Castle Street, not far from the family home. It was quite a financial loss at £2 10s, which equates to approximately £160 in 2022 [61]. In all likelihood, the stamps were probably part of the stock for the Clarence Tea House he was running.

The business was profitable, making £1727 in the 1926 season yet the Southsea Beach and Publicity Committee decided to put the Clarence Tea House and “all the tea houses, kiosks, and stalls, with the exception of the Southsea Castle Tea House…out to tender by public advertisement for the 1927 season [62].” Victor quickly seizes the opportunity.

Photograph of the Tea House on Clarence Esplanade. Taken in 1935 [63]

In 1930, Victor renews his tender for the Clarence Tea House, paying £150 to the Committee [64]. That summer, Welshman and repeat offender Arthur Bunt stole the collecting box containing 1s and 6d from the Tea House [65].

“The Clarence Tea House is to be rented next year to Mr. V. W. Durrant, who has been a satisfactory tenant for 15 years.”

Five years later, Victor offers a further £140 to secure the tenancy. Victor must have developed a valued and trusted relationship with the Beach and Publicity Committee as they refused a tender offer for an additional £21 [66].

Photograph taken from The Scotsman Newspaper in an article covering opening ceremonies [67]

The following summer was arguably the best season yet, with over 200,000 people visiting ships and dockside shows [68]:

“Visitors to the City arrived by special trains, by motor-coaches, cars and steamers. Portsmouth people swelled the happy throng, and even Dockyardmen and sailors endured familiar sights and acted as escorts for members of their families and friends. Everywhere the improvized [sic] grandstands for the numerous attractions were packed. The popularity of the massed bands, the cadets’ display, the Royal Marines King’s Squad, the crossing the line ceremony, the diving displays, and the cinemas showed no waning. Thousands upon thousands went on board the famous old three-decker H.M.S. Victory and contrasted her wooden walls with the mighty modern battleships which were also open for inspection. There were thrills experienced from the roar of guns, the swooping of aeroplanes, the sound of bugles, the playing of sea melodies [69]. ”

Victor undoubtedly would have been incredibly busy with crowds spilling out onto the Portsmouth seafront.

When war breaks out in 1939, Victor and Maria are still living on Gold Street, along with their youngest son Maurice, and their grandson Leonard Hawkins, who appears to be staying while his mother, Hilda, and siblings are visiting his father in Gibraltar [70].

1939 England and Wales Register [73]

Along with managing the Tea House, Victor was volunteering as an ambulance crew for the Air Raid Precaution (ARP). The British government recognised the need to prepare the civilian population for imminent war and passed the ARP act in 1937. Consequently, Victor may have responded to one of the many ARP recruiting campaigns or a local recruitment rally. As a veteran of World War One, Victor had received automotive training, so it is quite likely he was serving as an ambulance driver and a member of the casualty service. He would have been stationed in one of the 14 depots spread across the city from which “first aid parties set out to the scenes of bombing [71]” and may have undergone additional training arranged by the British Red Cross Society [72].

By early 1940, the Clarence Tea House had changed hands with the City Council, accepting a tender from Mr H. A. Lowe [74]. Victor’s decision to relinquish control of the business is completely understandable. He was now in his 60s and may have been finding the role of managing the Tea House quite physically demanding. The impact of war may have negatively affected business, and Victor may have also felt it necessary to focus on his contributions to the war effort.

ARP Recruitment Poster [75]

German bombing raids began in the summer of 1940. Portsmouth, home to the Royal Navy and countless other military and industrial installations, was a prime target. Victor and Maria would have experienced one of these raids firsthand on September 9th, 1940, when a bomb landed on the corner of Gold Street and Stone Street [76]. However, worse was to come when the Luftwaffe took aim and unleashed the most devastating aerial attack on the city ever. Over the course of several hours on the night of January 10th, 1940, over a hundred of German planes dropped 25,000 incendiary devices and hundreds of high explosive bombs on the city below. The electricity station and the water mains were the initial targets. Without power and water, the people of Portsmouth were almost powerless to stop the ensuing inferno, which resulted in more than 2000 fires that “lit up [the] sky like daylight [77]”. By morning, 171 people were dead and 430 were injured [78]. Much of the city was a smoking ruin.

Handley’s Corner, Palmerston Road c.1940 [79]

By 1941, the family has relocated to Marmion Road [80]. A mere ten-minute walk from Gold Street, Marmion Road appears to escape unscathed from the many bombing raids that continue to pummel the city.

As preparations for Operation Overlord accelerated, the movement of people in Portsmouth became increasingly restricted. In August 1943, Southsea seafront was declared a restricted zone, and from April 1944 Portsmouth was closed to all visitors. Portsmouth was to be the headquarters and a main departure point for the D-Day cross-channel assault. In early June, Victor may have seen the huge numbers of soldiers, vehicles, stores, and ammunition making their way through Portsmouth to South Parade Pier, Portsmouth Harbour, and Camber Quay as part of the Normandy invasion [81].

With the war over, family life returns to normal and in August 1946 Victor watches his youngest son, Maurice, get married to local girl Kathleen Nora Grimshaw.

Maria is by Victor’s side when he passes away a year later. He is suffering from an abnormal, possibly cancerous, growth on his larynx and chronic gout. Collectively, these conditions would have impacted his voice, making it hoarse; restricted his ability to swallow, leading to weight loss; and joint pain, which would have certainly impacted his mobility. As his death certificate highlights, Victor was exhausted. Yet he had led a unique life. At the age of 72, Victor had travelled the world, served his county many times, survived two global-scale conflicts, been a successful entrepreneur and businessman, and been a respected and loved family man, married for forty years with seven healthy children that outlived him.

Victor’s Death Certificate [82]

References:

[1] http://www.suffolkchurches.co.uk/kessing.html

[2] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/no-series/suffolk-history-antiquities/vol1/pp250-259

[3] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881; Class: RG11; Piece: 1900; Folio: 57; Page: 46; GSU roll: 1341458

[4] School shown on Victorian Ordnance Survey 6 inch to 1 mile Old Map (1888-1913) of Kessingland Suffolk, United Kingdom Map Centre Decimal Latitude/Longitude (WGS84): 52.413897, 1.704156. Available at https://www.archiuk.com

[5] Image taken from www.kessingland.onesuffolk.net/gallery/kessingland-bygone-days/

[6] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1891; Class: RG12; Piece: 1492; Folio: 21; Page: 29; GSU roll: 6096602

[7] The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services; Class: ADM 188; Piece: 534

[8] A New Story of the Sea. (1894, June 30th). Lowestoft Journal. Page 3.

[9] Press Reviews available in an 1897 edition of The Good Ship Mohock found at https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/4/40/The_good_ship_%22Mohock%22_%28IA_goodshipmohock00russ%29.pdf

[10] Conley, M. (2017). From Jack Tar to Union Jack: Representing Naval Manhood in the British Empire, 1870-1918. Manchester University Press

[11] Index of 19th Century Naval Vessels available at https://sites.rootsweb.com/~pbtyc/18-1900/U/05104.html

[12] Information on Royal Navy Ratings provided by The National Archives (UK) at https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/help-with-your-research/research-guides/royal-navy-ratings-further-research/#4-sources-for-men-entering-1853-1928

[13] Green, Allan C., photographer, & Green, Allan C. (1900). H.M.S. Volage. Image taken from http://search.slv.vic.gov.au/primo-explore/fulldisplay?vid=MAIN&docid=SLV_VOYAGER1648679.

[14] Information obtained from The Historic Dockyard Chatham website: https://thedockyard.co.uk/news/warship-wednesday-hms-alexandra/

[15] The Naval Manoeuvres. (1895, July 30th). The Standard. Page 3.

[16] The Naval Manoeuvres. (1895, August 8th). The Standard. Page 3.

[17] An Unfounded Report. (1895, August 17th). Southern Times. Page 4.

[18] Boating Disasters. (1895, August 31st). The Guardian. Page 6.

[19] Shipping Intelligence. (1895, November 15th). The Home News. Page 26.

[20] News from Gibraltar. (1895, November 26th.) The Globe. Page 8.

[21] Shipping Intelligence. (1895, December 26th.) The Journal of Commerce. Page 6

[22] Maritime Intelligence. (1896, January 1st.) Shipping Gazette and Lloyd’s List. Page 5

[23] Image taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Hong_Kong,_Entrance_to_the_port_by_Lai_Afong_c1880.JPG

[24] Naval Notes. (1896, January 16th.) Overland China Mail. Page 20.

[25] Lloyd’s List and Shipping Gazette Oversea Intelligence. (1896, February 5th.) Shipping Gazette and LLoyd’s List. Page 4.

[26] Lloyd’s List and Shipping Gazette Oversea Intelligence. (1896, February 17th.) Shipping Gazette and LLoyd’s List. Page 4.

[27] Rescue of a shipwrecked crew. (1896, April 15th.) St. James’s Gazette. Page 7.

[28] Steamer wrecked in the Mediterranean. (1896, April 11th.) The Western Evening Herald. Page 2.

[29] Information provided by the naval history wiki, The Dreadnought Project at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/Henry_Harvey_Bruce

[30] Information taken from the Royal Navy Communications Branch Museum website at https://www.commsmuseum.co.uk/dykes/signalschool/hmsignalschool1.htm

[31] The Jubilee Review of 1897. (1897, June 26th.) The Hampshire Telegraph. Page 8.

[32] Photograph from The News archive (https://www.portsmouth.co.uk/heritage-and-retro/retro/hms-victory-11-historic-royal-navy-images-from-the-past-3351491?page=2).

[33] The Channel Squadron. (1897, September 18th.) The Hampshire Telegraph. Page 8.

[34] Lloyd’s List. (1897, September 14th.) Shipping Gazette and Lloyd’s List. Page 7.

[35] Naval and Military Intelligence. (1897, September 24th.) The Morning Post. Page 5.

[36] Seamen Court-martialled. (1897, October 16th. ) The Hampshire Telegraph. Page 8.

[37] Lloyd’s List. (1897, December 15th. ) Shipping Gazette and Lloyd’s List. Page 4.

[38] Hampshire, Portsmouth, Portsea Island Rate Books. (1901). Archive reference DT/R/3/38. Folio Number 98.

[39] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901; Class: RG13; Piece: 1003; Folio: 105; Page: 2

[40] Hampshire, Portsmouth Trade Directories 1863-1927. (1903-04). Page 196.

[41] Hampshire, Portsmouth Trade Directories 1863-1927. (1905-06). Page 360.

[42] Ordnance Survey. (1888-1913). Portsmouth [Map]. 1:10,560. County Series. Available at https://maps.nls.uk

[43] Hampshire, Portsmouth, Portsea Island Rate Books. (1906). Archive reference DT/R/3/48. Folio Number 39.

[44] Portsmouth Police. (1906, June 19th.) The Evening News. Page 5.

[45] ‘Victor William Durrant’ (1907). Certified copy of birth certificate for Victor William Durrant, 22 March 2022. Application number 12604072/2. Alverstoke Register Office.

[46] Hampshire, Portsmouth Trade Directories 1863-1927. (1907-08). Page 513

[47] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911; Class: RG14; Piece: 5616; Schedule:170.

[48] Information taken from http://michaelcooper.org.uk/C/clarence.htm

[49] Image taken from https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Clarence_Pier,_Southsea,_ca._1914.png

[50] Information taken from https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/private-lives/yourcountry/overview/conscription/

[51] Hampshire, Portsmouth Military Tribunals 1916-1919. (1917). Archive Reference: DC/45/1/B2/2. Page 5.

[52] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Medal card of Durrant, Victor W, Army Service Corps M/399713, WO 372/6/130241

[53] Victor’s role is speculative. His Army service record was lost during the blitz. More than half of all World War One service records were destroyed in September 1940, when a German bombing raid struck the war Office in London.

[54] Image taken from https://www.rlcarchive.org/ContentRCT

[55] Census Records. England. Portsmouth. 19 June 1921. Durrant, Victor. RG15. https://www.findmypast.co.uk accessed 5 June 2022.

[56] Hampshire, Portsmouth Trade Directories 1863-1927. (1922). Page 702

[57] Hampshire, Portsmouth Trade Directories 1863-1927. (1923). Page 766

[58] Southsea Fair. (1923, May 24th.) The Evening News. Page 5.

[59] Two new cities. (1926, April 24th). The Evening News. Page 10.

[60] Data obtained from https://weather.sumofus.org

[61] Projection calculated using the UK future inflation calculator at https://www.in2013dollars.com/uk/inflation/1926?amount=2.50

[62] To-Day. (1926, October 25.) The Evening News. Page 6.

[63] The exact location of Clarence Tea House is unknown, but the most likely candidate is shown in the photograph. Image taken from https://bygone.co.uk/archive/tea-kiosk-clarence-esplanade-1935.631/

[64] Southsea Lettings. (1930, January 22.) The Evening News. Page 5.

[65] Plea for leniency fails. (1930, August 29th.) Hampshire Telegraph and Post. Page 19.

[66] By the Way. ( 1935, December 16th.) The Evening News. Page 8.

[67] Impressive Opening Ceremonies at The Berlin Olympiad. (1936, August 3rd.) The Scotsman. Page 12.

[68] Information obtained from the Dockyard Timeline at https://portsmouthdockyard.org.uk/timeline/details/1936-navy-week

[69] Bigger Crowds Than Ever For Navy Week. (1936, August 7th.) Hampshire Telegraph & Post. Page 14.

[70] The National Archives; Kew, Surrey, England; BT27 Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and Successors: Outwards Passenger Lists; Reference Number: Series BT27-162658. Hilda and her children do not return to the UK until after the 1939 Register has been completed.

[71] Portsmouth First Aid Posts Ready. (1939, September 1st.) Hampshire Telegraph & Post. Page 15.

[72] Public Notices: Air Raid Precautions. (1939, January 12th.) The Evening News. Page 6.

[73] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1939 Register; Reference: RG 101/2279J

[74] By the Way. (1940, February 16th.) The Evening News. Page 4.

[75] Image taken from IWM. © IWM Art.IWM PST 0147

[76] Data shown on the Portsmouth Museum’s Bomb Map at https://portsmouthmuseum.co.uk/collections-stories/80th-anniversary-of-the-blitz/the-portsmouth-bomb-map/

[77] John Welch’s diary account available at https://www.welcometoportsmouth.co.uk/1941-portsmouth-blitz-diaries.html.

[78] Account details for January 10th 1940 obtained from https://portsmouthmuseum.co.uk/collections-stories/80th-anniversary-of-the-blitz/portsmouths-air-raid-reports-from-the-second-world-war/, https://liblog.port.ac.uk/blog/2016/01/14639/ and https://dalyhistory.wordpress.com/2011/01/11/the-portsmouth-blitz-70-years-on/.

[79] Image taken from The News archive (https://www.portsmouth.co.uk/heritage-and-retro/retro/35-photos-capture-portsmouth-during-the-blitz-2910290?page=4).

[80] Engagements. (1941, April 9th.) The Evening News. Page 4. Victor and Maria’s address is listed in the engagement notice for their son, Maurice.

[81] Information taken from The D-Day Story website (https://theddaystory.com).

[82] ‘Victor William Durrant’ (1947). Certified copy of death certificate for Victor William Durrant, 10 December 1947. Portsmouth Register Office.