Prisoner Of War: Robert Edward Butt (1886-1969)

Robert was born on April 7th 1886 at Clark’s Yard, Oundle, Northamptonshire, UK. The youngest child of parents George William Butt (29 years old), an agricultural labourer, and his wife Charlotte Odam (36 years old), Robert had at least five siblings (Eliza Ann Odam, 1875-1959; Emily Rebecca Butt, 1876-1959; William James Butt, 1879-1964; John Thomas Butt, 1881- ; Mary Ann Elizabeth Butt, 1884-1953).

Robert Edward Butt’s Baptism Record

Robert was baptised three years later on August 2nd 1889 in the parish of Oundle, Northamptonshire by the Assistant Curate, Francis L. Dennan. Oundle is an ancient market town situated on the River Nene. The tall spire (210 feet high) of St Peter’s Church can be seen across the water meadows. In 1887, John Bartholomew’s Gazetteer of the British Isles described Oundle like this:

“Oundle, market town, par., and township with ry. sta., Northamptonshire, on river Nen, 13 1⁄2 miles SW. of Peterborough and 98 miles from London – par., 5300 ac., pop. 3073; township, pop. 2953; town, pop. 2890; P.O., T.O., 1 Bank. Market-Day, Thursday. The name is a corruption of Avondale. In the vicinity are several mineral springs impregnated with iron; one of these sends forth a singular noise, which gives it the name of the “Drumming Well.” Quantities of lace are made by the inhabitants.”

By 1891, Robert is living with his family at 86 North Street in Oundle. His neighbours include other working-class families, including the Pridmore (Bricklayer), Pulford (Farm Labourer), Watkins (Brick maker) and Roe (Coal Carman) families.

Looking along North Street, Oundle towards Market Place. Image taken around 1904 (https://www.peterboroughimages.co.uk).

At the age of 14, Robert is working with his father and both are listed as milk cart drivers for a local farmer in the 1901 census. The family hasn’t moved far and is living at 142 North Street, Oundle.

1891 Census

1901 Census

Between 1903-1904, Robert enlists with the West Yorkshire Regiment (Private 7545), most likely as an infantry soldier signing up for a period of 6 years before joining the Army Reserve.

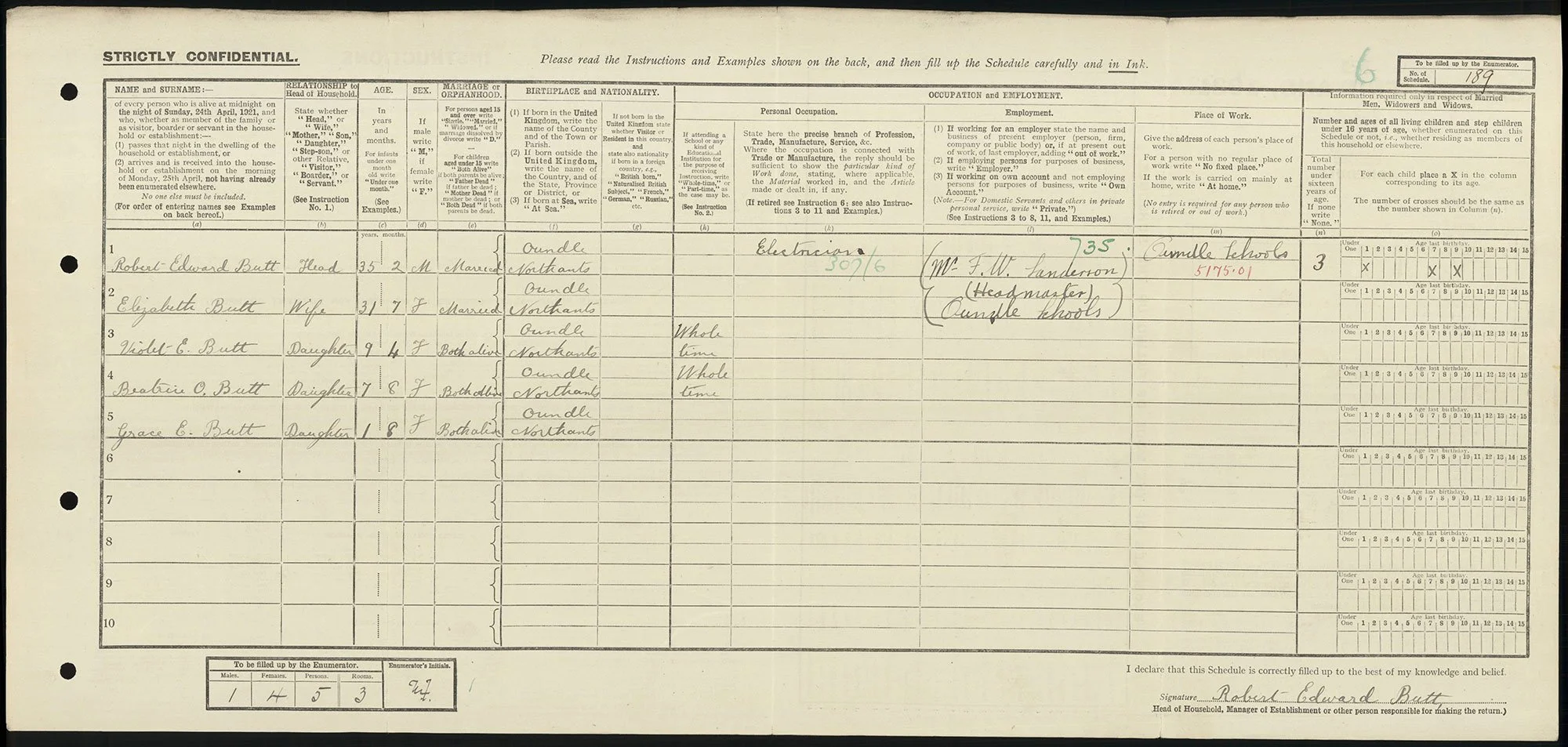

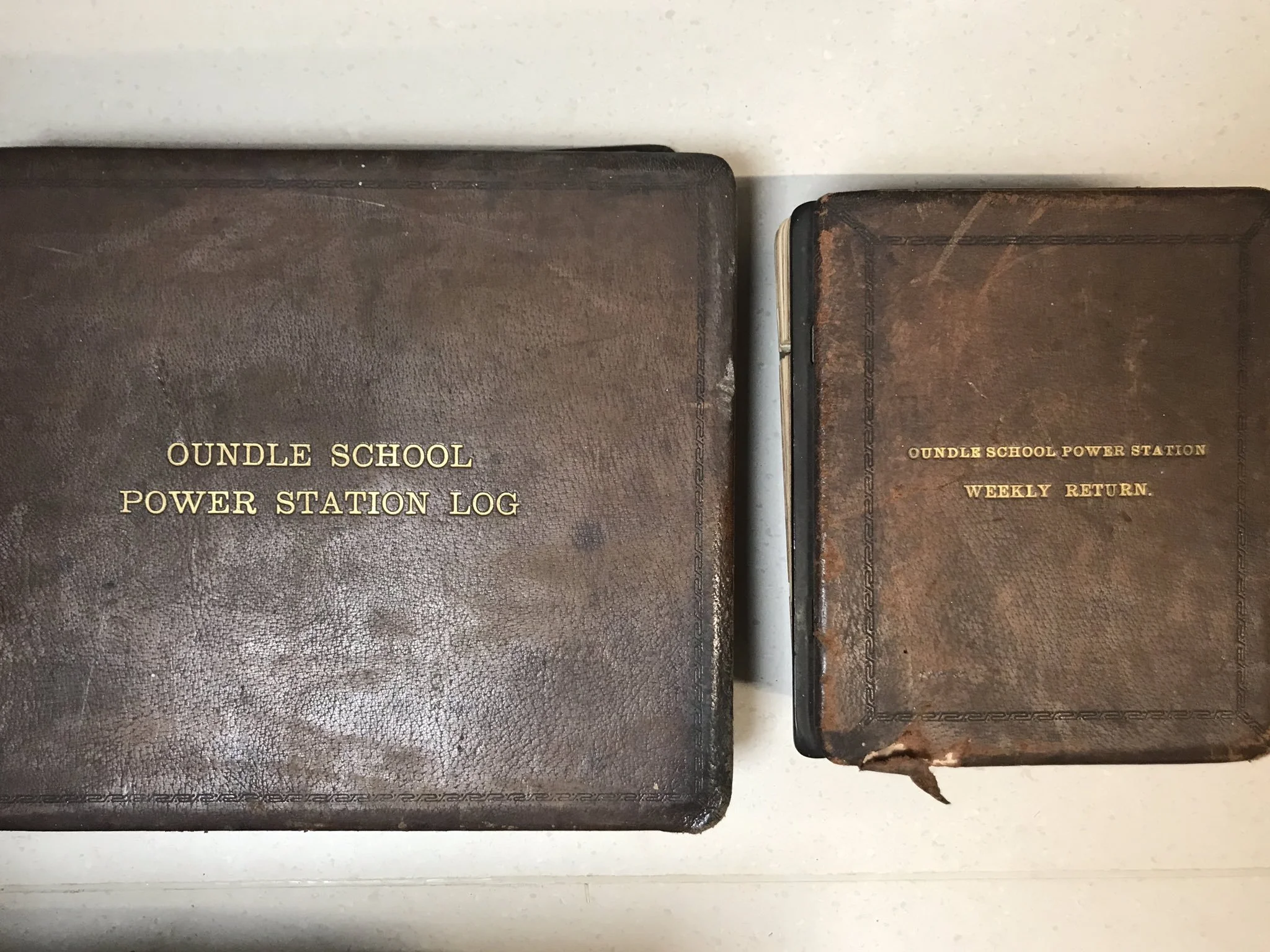

In 1908, he begins employment at Oundle School as part of the maintenance and engineering staff and was in charge of the school’s power station. Under the leadership of Frederick William Sanderson, the Headmaster of Oundle School, Robert watches the rapid expansion of the school over the next few years as it becomes a leading establishment for science and engineering education, befitting its status as one of the country’s major public schools.

On August 2nd 1909, at the age of 23, Robert marries Elizabeth Jacobs, a young and single local woman and the daughter of a bricklayer, in the parish church. Witnesses include Elizabeth’s brother and sister, William and Agnes Jacobs. By 1911, the young married couple is living in Morris Yard, Oundle and within a year they have their first child, Violet Elizabeth (born February 23rd 1912).

1911 Census

Elizabeth is pregnant with their second child when war breaks out on July 28th 1914 and Robert, as a reservist, is immediately called up. By August 7th 1914 he is already stationed at Lichfield before making his way to Dunfermline along with 25 officers and 991 other ranks. Between August 9th 1914 and September 8th 1914, the West Yorkshire regiment’s 1st battalion is inoculated and travelled to Southampton via Cambridge. Arriving late at night, the battalion embarks on the British cargo ship the SS Cawdor Castle, a steel screw steamer, and prepares to set sail the next morning.

The SS Cawdor Castle arriving in France in 1914 (www.clydeships.co.uk)

At 6:15 am the vessel makes its way across the English Channel to St Nazaire harbour on the west coast of France, carrying soldiers, horses, vehicles and bicycles to reinforce the British Expeditionary Force on the Aisne. The group catches a train to Coulommiers outside of Paris and marches onward to Chateau Thierry some 26 miles away on September 15th 1914, stopping for tea along the way. From there they march in heavy rain to Bourg via Tigny, Chaerise and Nampteuil, and arrived at 7:00 am on September 19th 1914. Within 5 hours, the village was being shelled. The battalion proceeded to Troyon, located on the southern slope of the Chemin des Dames ridge and north of the River Aisne, and after dark, relieved the Coldstream Guards in the firing line and support trenches.

British trenches at the First Battle of the Aisne, September 1914 (www.iwm.org.uk)

Robert, with his fellow soldiers, spent the night improving the trenches and constructing overhead cover before shell and infantry fire began at 3:30 am. Heavy fighting ensued, leaving 78 men dead, 112 wounded and 444 missing, most of which were taken prisoner when the Germans advanced under cover of a white flag. Robert had been on the frontline for a little over 24 hours.

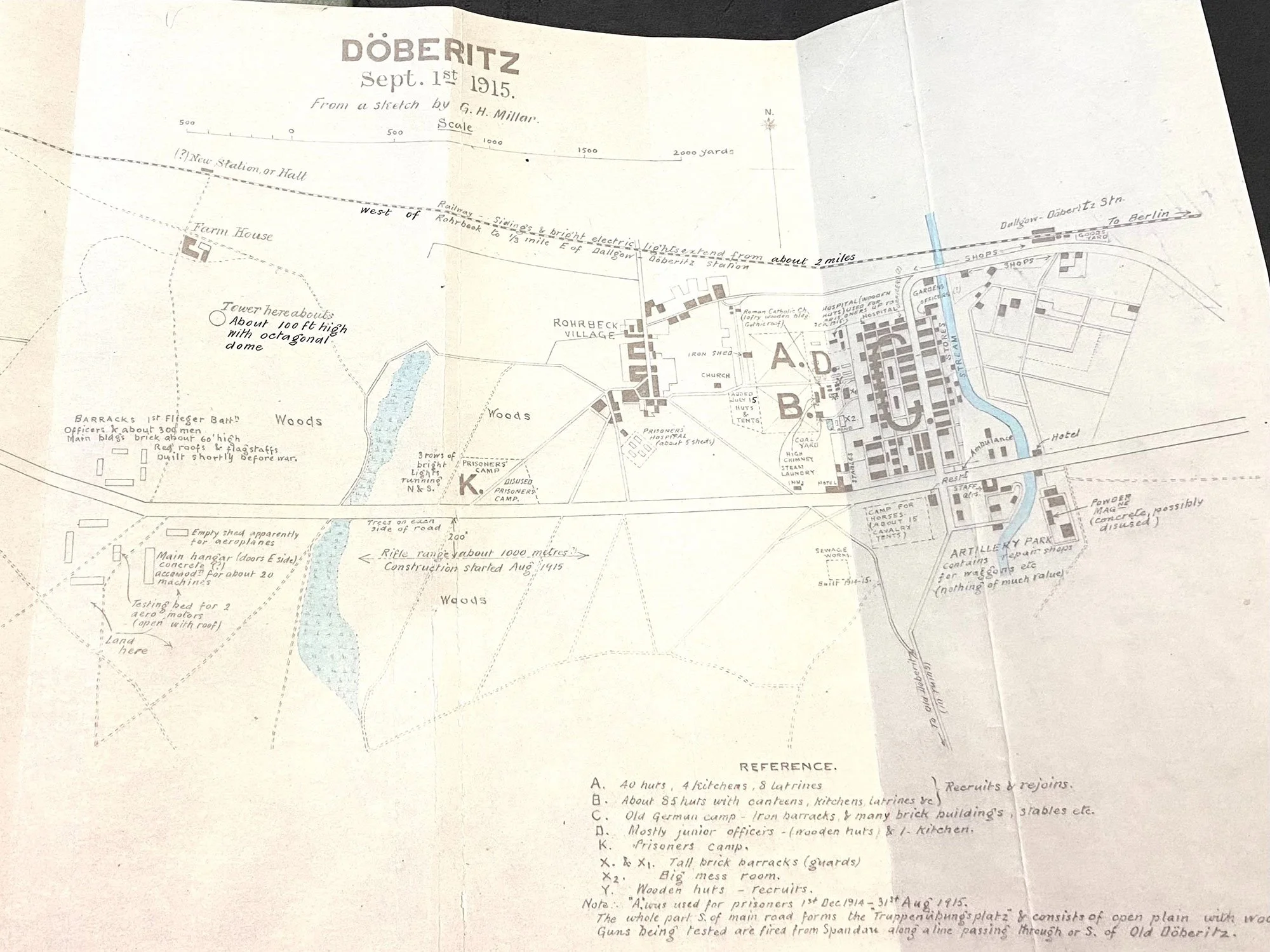

Robert was sent to Döberitz camp shortly after his capture. One of many Mannschaftslager (enlisted men’s camp) dotted across Germany, Döberitz was less than 20 miles from Berlin and Robert likely had to travel by cattle truck over several days to reach his destination. Various reports from the time highlight the withholding of food and abusive treatment, which included “spitting in their faces,” and being struck “with the butt end of…rifles” by German guards during the journey. This experience would be the first hint of things to come. Fellow Döberitz detainee, Private Hookham, reported:

“In November 1914 I saw Whitehead, R.N.D., killed. To get to the cookhouse we had to go through a gate; we were lined up by guards and corporals with whips in their hands, and if we did not keep fours we were whipped into line. That morning the guard at the gate shot into the crowd, the bullet went through Whitehead in the region of his heart, and then wounded a Russian. There was no disorder or reason for the guard’s action at all. I was five yards from Whitehead when he was shot. He died immediately…

While I was at Döberitz, W. Cannell, No. 6060, 1st Battn. East Surreys, told me about A. Sharpe, R.N.V.R., London, whom I knew. He was tied up to a post for punishment, and the German guard opened his shirt so as to let the mosquitos get at him. He was taken down unconscious, and afterwards an under-officer tried to choke him, but some of our men went for him. The result of this treatment was that Sharpe suffers from epileptic fits, and when these fits are on him the marks of the man’s fingers come out on his throat.”

Colonel Alberti was the Camp Commandant and for the most part, was considered reasonable. An early camp inspection (August 1914) by James W. Gerard, the US Ambassador to Germany, found conditions entirely satisfactory. By contrast, the other Germans; Feldwebel Mozart, Unter-offizier Schneider, Feldwebel Podlavski, Unter-offizier Heider and Unter-offizier Sassoff brutalised the British soldiers and there were occasions where “several prisoners were shot by the Germans at various times without any justification”. Punishments would also be meted out and included flogging, solitary confinement and the withholding of food and letters.

Conditions rapidly worsened as the number of prisoners grew:

“On arrival at Döberitz the R.N.D. and Marine prisoners were placed in the Camp marked “Disused Prisoners’ Camp” on plan. The adjoining camp on the other side of the road (marked “Prisoners’ Camp”) was occupied by some 2500 soldiers of the Expeditionary Force, who arrived in Döberitz (for the most part) some six weeks earlier than the R.N.D. About 1000 French and Belgian prisoners joined the camps soon afterwards, and about 5000 Russians at the beginning of November. The conditions of life here were very primitive, the prisoners being housed in tents made from torn canvas stretched on rickety wooden frames with bare earth floor; washing had to be carried out in a horse trough out of doors, and the latrine accommodation (open trenches) was quite inadequate. The food was at first fairly good in quality, though being very watery it had a very bad effect on the health of the prisoners. Later on the food degenerated in quality progressively.”

Map of Döberitz Camp from a sketch by G.H. Millar (The National Archives of the UK)

Upon Robert’s incarceration, he was quickly assigned a role in the Engländer Kommando unit, E.K.1, and may have been assigned work in quarries, mines, factories or farms as part of the German war effort.

October 1914 comes and goes. Robert misses the birth of his daughter Beatrice Olive Butt (born October 21st 1914) and it will be over four years before he reunites with his family. By December, Robert’s parents are aware of his imprisonment, which is reported in the Northampton Mercury:

“The parents of Private Robert Butt, 1st Battalion West Yorkshire’s, and of Private George Jacobs, 1st Northants, both of whom are prisoners, have heard from them, saying they are well. They complain of not hearing from their friends.”

It’s most likely around this period that Robert sends home a postcard during a brief stay at the Frederichsfeld camp. He appears to be in good health and according to Sergeant A.J. Ollerton of the Coldstream Guards “this camp was not so bad as the others”.

Postcard sent to Robert’s father, George Butt, showing Robert at Fredrichsfeld camp

Parcels from home begin arriving at Döberitz camp by February 1915. Among likely correspondence from family and friends during his internment as a prisoner of war, Robert particularly cherished letters sent by F.W. Sanderson, his friend and employer. Years later he would proudly show these letters to others.

As a reprisal for the employment of German prisoners in France by the British government, E.K.1 are sent to Libau (Liepāja), a city in western Russia (now Latvia) on the Baltic Sea. Libau was viewed as a major logistics base for the German Army on the Eastern Front and on May 8th 1916, Robert, along with 1000-2000 fellow British prisoners, left Döberitz and made the four-day journey in cattle trucks, which “became terribly insanitary before long”.

Supplies being loaded onto ships in the harbour of Libau during WW1 (www.iwm.org.uk)

Work at Libau docks involved a lot of heavy lifting manual work. It employed many of the prisoners in unloading provisions from ships, and working in the slaughter-houses, fisheries, and straw-barns:

“My company was No. 4, about 500 of us. We were sent to Libau. The others were sent to work on railways. At Libau we were put into a big factory. The first three months we had to sleep on the boards. There was snow on the ground at first; very cold wind and gales. We had our own blankets. It was fairly warm in the warehouse at that time. We had to unload boatloads of flour in the docks and to work in the prison stores shifting cases of provisions. At first we were knocked about a lot because we complained that the work was too heavy. None of us refused to work. If we had done so, I believe they would have shot us.”

As well as hard labour, Robert and his fellow POWs, over the next ten months, experienced brutal treatment at the hands of the German guards.

“Tins are opened so that the contents often go bad before the owner receives it…Men who refused to work were locked in a shed, lashed with dog whips by German officers, and…tied to trees by their wrists, with their feet off the ground, and kept in such a position for eight hours…Men who were sick were forced to work at the point of the bayonet. Parcels were stopped for a month or six weeks at a time. Any man who had more than one suit of clothes or one pair of boots had them taken away.”

On February 23rd 1917 at 10 pm, Robert and Sergeant-Major Alexander Gibb along with the rest of No.4 company are sent to Mitau (Jelgava) by cattle trucks as retribution for actions by the Allied government. This included employing German prisoners close to the front line.

Map of established Soviet power in Latvia from 1917. German-occupied territory designated by dashed lines (www.stradnieki.org)

Arriving the following evening, the company stay overnight in a Russian prisoners’ concentration camp before falling in at 5 am. A squadron of Uhlans, a German cavalry unit, escorted the company along the River Aa, which flows from Mitau to Riga, to the village of Latchen, near Kelzien. It took 12 hours or so to march 30 km through the frozen wilderness owing to the depth of snow, which was 6 inches deep. The reprisal camp was located some 5-6 kilometres behind German front lines and was within the Russian firing zone, close enough for the area to be hit occasionally by shells.

Abuse was constant during the journey:

“We started the march, and we never stopped once until dinner time, and whenever a space was too large in a section, the Uhlans hit us with lances or whips. Men were struck behind the neck and were bleeding, and before dinner time about 50 had fallen out and were lying unconscious on the roadway.”

The company meet by German commander, Lieutenant Prahl, who kept them “standing in the snow for two hours until all the stragglers had come in” before providing quarters in a single large cavalry tent. Conditions were particularly deplorable:

“A barbed-wire fence closely encircled this tent. There was no drinking or washing water; we had to do what we could with snow for these purposes, nor where there any buckets or anything to store water in. Cooking water was brought from the river daily by a fatigue party in the field cookers. Rations were just enough to keep us alive… A large number of the men had no blankets. We slept in two layers on wire netting stretched on poles…Loose old fibre, which had been lying in the snow and was all wet, was spread over the wire netting.”

Robert and his camp mates are effectively starved over the next four months. The rations provided were barely enough to keep the men alive as they are put to work between the lines “felling and carrying timber, which the pioneer troops used for the machine-gun emplacements, road making…ice breaking, trench digging.” Men received one loaf of bread every seven days, one bowl of soup, and two cups of coffee per day. Food is extremely limited and desperation quickly sets in:

“The men were so hungry that they would pick up any bones when they were out to gnaw when they got home. One man brought back a piece to eat, and when he got back it was found to be part of a skull with the hair on.”

The parties in the trenches daily came under trench mortar and shell fire, sometimes working within 60 metres of the Russian stockade. Despite poor Russian ammunitions there were a number of casualties from shrapnel and at least one man “was shot through the stomach by a Russian sniper.” Regardless of this imposing threat, men were knocked about and even bayoneted, for being slow or not working to the satisfaction of their guards. As time went on, there were growing numbers of men too weak to work. One of these, Private Skett of the Coldstream Guards, was shot dead by a German sentry when he collapsed several times from exhaustion.

Sub-zero temperatures in the region are typical in late February and early March and many men suffered terribly from frost bite:

“I had my leg swollen to twice its proper size through frost. I had no feeling in it. I could only just manage to crawl along. They made me work all the same….I saw a man, named Nixon (Duke of Wellington’s Regiment) take off his boots. He found he had a toe missing. He was greatly surprised. He looked, and found the toe hanging by a thread of skin. He pulled it off and threw it away….His feet were in a terrible state. There was matter running out. They smelt very bad…I also remember a man, named Fletcher (South Lancashire Regiment), take off his boots when we had the bath. The whole of one of his feet was black, and looked dead…When he got into the hot water it was very painful. Tears ran from his eyes with the pain…We saw he could hardly stand, so we helped him back and put on his clothes for him. He fainted while we were putting on his clothes.”

The cold was unbearable and extra clothes made little difference. Some died from frost, one was found frozen to the canvas of the tent, and several others had arms and legs amputated owing to frostbite. By the end of March, over 200 men were admitted to the hospital in Libau in such a terrible state looking like “bags of skin and bone, with frost-bitten feet, and mostly suffering from nephritis or kidney complaints, with swollen legs, brought on by exposure and hardships”. By mid-April only 77 men from the original contingent of 500 remained at the camp. Of these, 47 were marked by the camp doctor as unfit to work.

As the weather improved and the ice thawed, the first consignment of parcels arrived along with a new German commanding officer. Conditions improved greatly but not before more than 50 men had died of starvation, 30 men were killed by the Germans and 10 men had died of wounds received from Russian gun fire. This included three of Robert’s regimental colleagues, Private Barlow, Private Boyington, and Private Goodall who, after inflicting a self-inflicted wound, subsequently died following amputation of his arm.

On June 9th orders were received, which saw No.4 company withdrawn and returned to Libau. After months of horrific treatment many could not be “considered sane men.” The impact on the survivors would be long-lasting:

“It would be beyond the powers of any man, no matter how able or fluent, to describe, in writing, the impression it left as you gaze upon these human wrecks, starved, frozen and unwashed. Simply a frame of bones covered with skin, breathing and looking at you with eyes sunk deep into their sockets, and worst of all, when you spoke to some of them their answers were quite unintelligible, thus betraying that their tormentors had gone to the very extreme and driven them almost to insanity.”

Robert was one of the remaining 72 men that left the reprisal camp on June 10th, surviving 106 days of some of the worst prisoner of war treatment in World War One. Company Sergeant-Major Gibb highlights the names of survivors in his statement to the Committee on the Treatment of British Prisoners of War, Robert is among them:

“I desire also to record the names of the 72 N.C.O’s and men who lasted out the whole period of reprisals with me. The fact that they did so was entirely due to their determination not to give in, but to see the business through at all costs, and to their efforts to take care of themselves to this end.”

There was brief respite at Libau. In less than four weeks the usual activities began. There had only been a short period of restricted work to allow recovery.

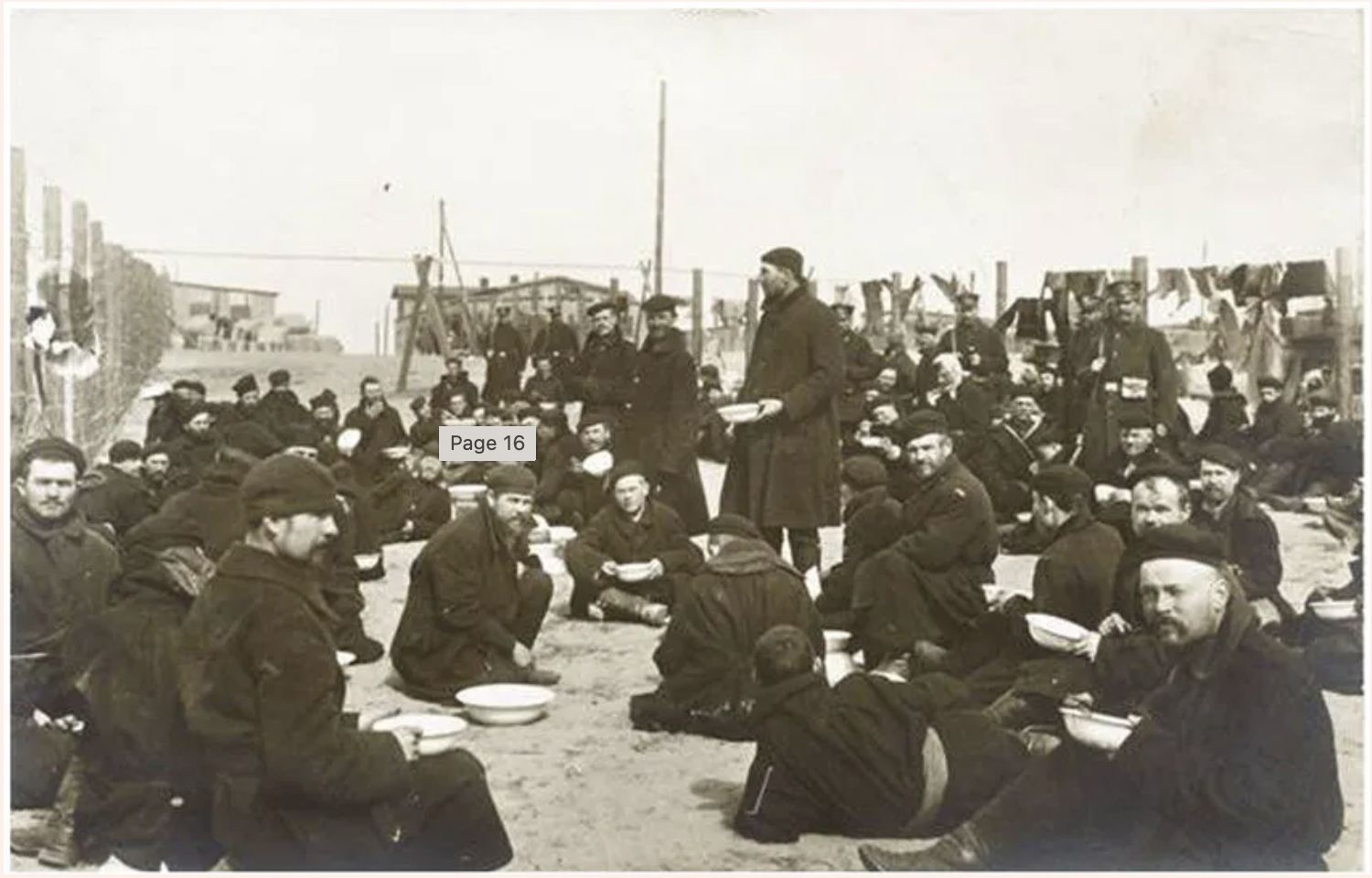

An archive photograph of prisoners of war at the Czersk camp (Dawid Kobiałka, Creativity behind barbed wire (2018))

At the end of October all four companies (~1700 men) mustered at Libau and Robert, as part of E.K.1., embarked aboard the merchant vessel SS Badenia and set sail for Danzig41. From there they proceeded onward to Czersk, a large POW camp in West Prussia (now Poland) where mostly Russian and Romanian soldiers were detained. Arriving at 5 am on November 4th, the men were immediately filled with dread:

“Here untold misery awaited us. We were put into dilapidated dug-outs which were in a state of decay; snow, rain, wind and frost penetrating into every crevice….The following took place:- Stripped; all clothes and belongings taken from us to be disinfected; inspected by a Russian with a huge magnifying glass looking for vermin; all hair cropped short like a felon; bathed in a filthy place in which I would not put pigs; put into a room naked and there remained for four or six hours waiting for our clothes to come from the fumigator.”

Conditions were again abominable. Camp huts built half underground were damp and cold, providing little shelter, and diseases like Typhus were rife. Between 4000-9000 Russian soldiers are estimated to have died at Czersk. Thankfully, the War Minister in Berlin issued an order that all the English prisoners in occupied territory in Russia were to be returned to Germany and Robert was swiftly transported to Chemnitz, in Saxony, after just a few weeks. Robert is recorded in Chemnitz on February 8th 1918, along with William Buttrey from the West Yorkshire regiment, who had also been held at Mitau.

E.K.1. was quickly split into various working parties, which were distributed over the Saxon coalfields. It’s likely that Robert would have been one of many men ruthlessly exploited to work the vast lignite (brown-coal) deposits across the Central German coalfields in and around Chemnitz, Zwickau, Leipzig and Mittelsaschen. Such labour would have been undoubtedly difficult, unpleasant and, at times, dangerous:

“The men at Chemnitz are having a terrible time; in fact, they say the treatment is as bad as in 1914. The men in parent camps are all right, but it’s those on commando who suffer so terribly. At Chemnitz they are working 900 feet underground. If they refuse they are knocked senseless, and taken down to where they recover consciousness; they are made to work till their piece of work is done, and starved until it is finished.”

It’s unclear when Robert was repatriated, but for the majority of Allied prisoners of war their captivity did not end with Armistice Day. Some had to wait another month or two before reaching home and achieving freedom. However, by January 1919, Robert was demobilised and safely returned to the UK to civilian life. A recipient of the Victory Medal and British War Medal, he is placed on the Army Reserve Z List, and obligated to return to service if called upon. It will take another year before this requirement is abolished.

Almost immediately upon his return, Elizabeth falls pregnant with their third daughter and Grace Ethel is born in October 1919. By June 1921, Robert had resumed his role at Oundle School, working as an electrician and managing the school power station. Among his many tasks, Robert diligently kept records of the school’s electricity production.

1921 Census

Oundle School Power Station Logs

After many hard years of captivity, Robert settles into town life quickly. Robert and Elizabeth go on to have another two children. Eileen is born in 1922 and their only son, Robert Edward, is born ten years later, in the autumn of 1932.

Robert (centre) and Elizabeth Butt (right) with one of their daughters. Photograph taken outside the former Oundle School Science Block on Glapthorne Road (Image provided by Christine Nix)

Robert remains a valued member of Oundle School for a further seventeen years before retiring in 1949. Regarded as a pillar of the community, Robert (Bobby) is fondly remembered with “an ability to tell a good story, usually with an amusing sequel…one has only to stop him in the street and with a roguish smile and he will begin to narrate.”

Despite his obvious frailty and his progressive loss of hearing, Robert spends much of his time outside on long walks with his dogs in the Oundle countryside.

In 1954, Robert and Elizabeth make the trip to the south coast and watch their youngest child, Robert, marry Brenda Pluck in Portsmouth, Hampshire, UK. Within another five years, Robert and Elizabeth celebrate their own 50th wedding anniversary.

Robert Butt (second from left) and wife, Elizabeth (third from right), on their son’s wedding day

Over the next ten years, Robert likely suffers periods of ill health and may have experienced shortness of breath, coughing and chest pain resulting from advanced lung cancer, which had spread throughout his body. In 1969, he is admitted to Park Hospital in Wellingborough, a red brick Victorian building that was originally part of the Wellingborough Union Workhouse. It is relatively warm (19°C) but a windy and cloudy day on July 3rd 1969 when Robert finally passes away, a fighter to the end. He is 83 years old.

Death certificate for Robert Edward Butt