Conspicuously Heroic: Frederick Tinsley Birchall (1881-1963)

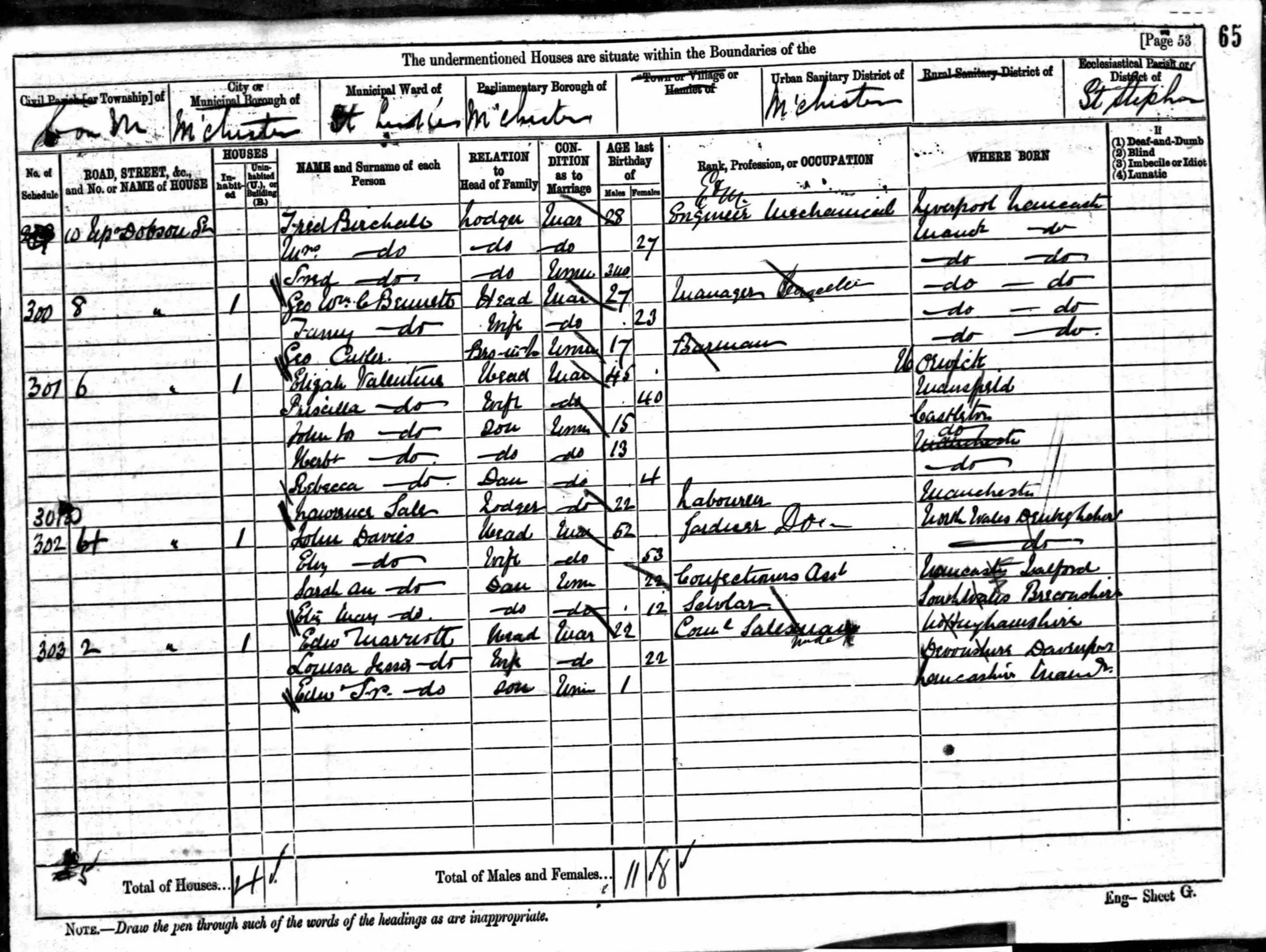

Born on Monday January 3rd, 1881 at 10 Upper Dobson Street, Frederick Tinsley Birchall was the first child born to Frederick Birchall and Alice Hyde [1].

Birth Certificate of Frederick Tinsley Birchall [1]

Upper Dobson Street was situated in the northern part of Chorlton upon Medlock, near Elton Street, Upton Street, Everton Road, Freme Street and Baker Street. The local pub, known as the Dog and Partridge, could be found on the corner with Elton Street advertising Empress Brewery Ales and Stouts [2].

Chorlton upon Medlock, a once small country village, was situated along the banks of the River Medlock before being incorporated into the city of Manchester as the Industrial Revolution took hold. Thousands upon thousands flocked to Manchester for work, including Frederick’s father. Vast swathes of the city were transformed into impoverished slums. Salford, Hulme, and substantial portions of Chorlton and Ardwick saw the proliferation of textile mills, substandard housing, severe overcrowding, and unsanitary conditions, resulting in alarmingly elevated rates of disease and death due to typhus, typhoid, and diarrhoea. Infant mortality was particularly high reaching 170-200 deaths per thousand live births between 1880 and 1890 [3].

The majority of the 19th-century immigrant workforce in Greater Manchester endured unstable, meagre-paying jobs and resided in cramped, damp, poorly illuminated, and inadequately ventilated lodgings. Dwellings like back-to-backs, court residences, and cellars were common, often shared by numerous families. At the time of Frederick’s birth, the family were lodging with the Tollett family [4].

Map of Charlton upon Medlock, Manchester published in 1891 [5]. Upper Dobson Street is marked with a red box.

Slum housing in Chorlton upon Medlock, Manchester c. 1895 [6]

By 1888, the young family had expanded and Frederick now had two younger brothers, Stanley (born 1883) and Albert Edgar (born 1888), and two sisters, Annie (born 1885) and Edith (born 1887).

1881 Census [4]

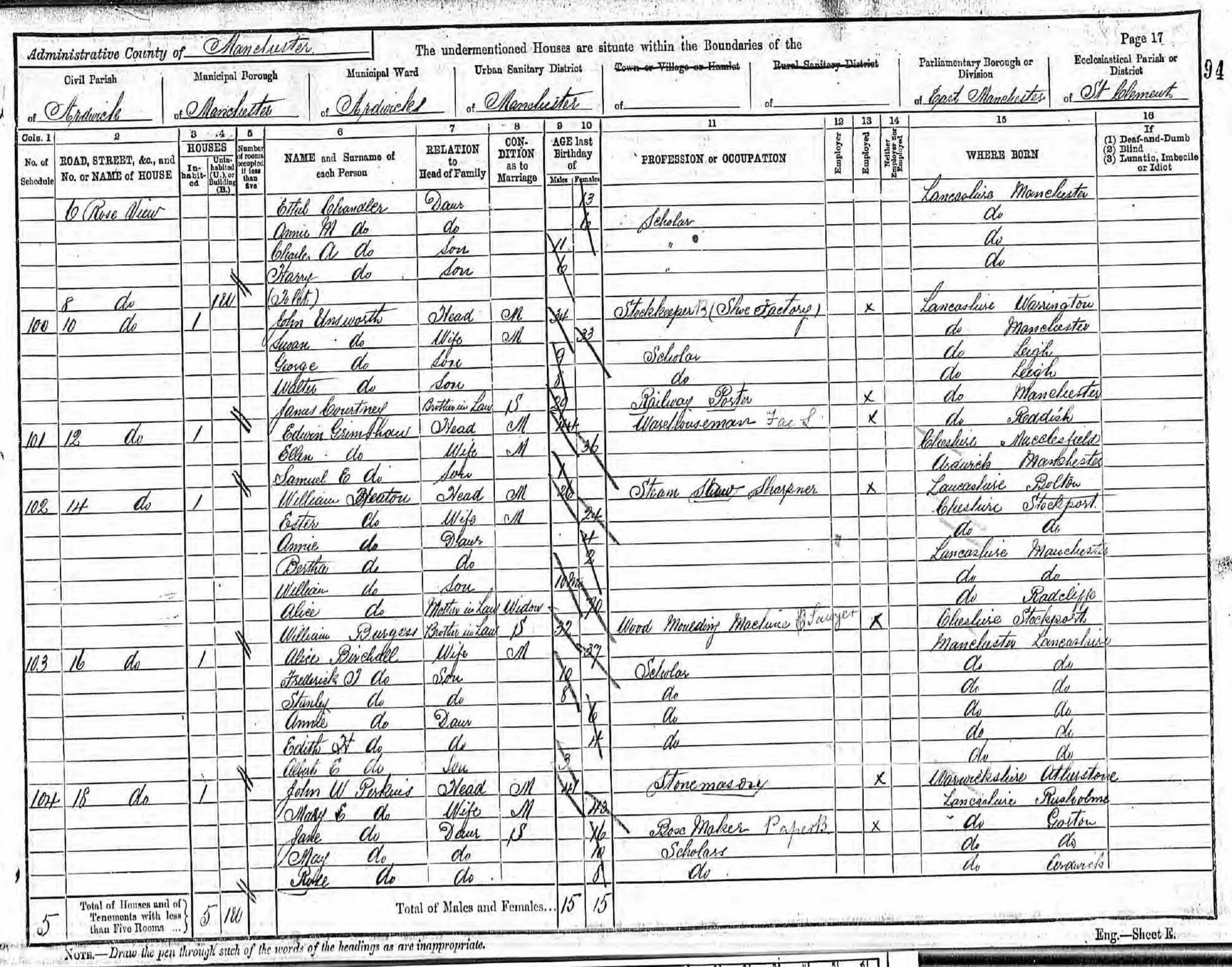

A growing family needed more space and this likely necessitated the move to 16 Rose View in Ardwick [7].

Map of Ardwick, Manchester published in 1891 [8]. Rose View is marked with a red box.

Parts of Ardwick were substantially affluent, particularly the area around Ardwick Green, which was the location of many Georgian and Regency-style homes belonging to cotton magnets and merchants. However, Ardwick was also home to numerous textile mills and factories including brick works, chemical plants, boiler works and a rubber factory. Consequently, the area was marked by slum housing and widespread poverty. Therefore, it is unlikely that the young Birchall family saw a significant improvement in living conditions.

Rose View was extremely close to one of the Manchester Carriage and Tramway Company depots. The site in Ardwick had several stables homing many of the horses used to pull the horse-drawn tram service across Manchester and Salford [9]. Frederick and his siblings would have been very familiar with the musky scent of the horses, the rich aromas of wood and leather, and the calming sounds of hooves on the ground as the trams regularly made their way along Grey Street.

A horsecar on Manchester’s tramway system c. 1895 [10]

Frederick’s father was absent at the time of the 1891 census [11]. As the listed tenant for 16 Rose View [12], it’s unclear why he was missed by the enumerator.

1891 Census [11]

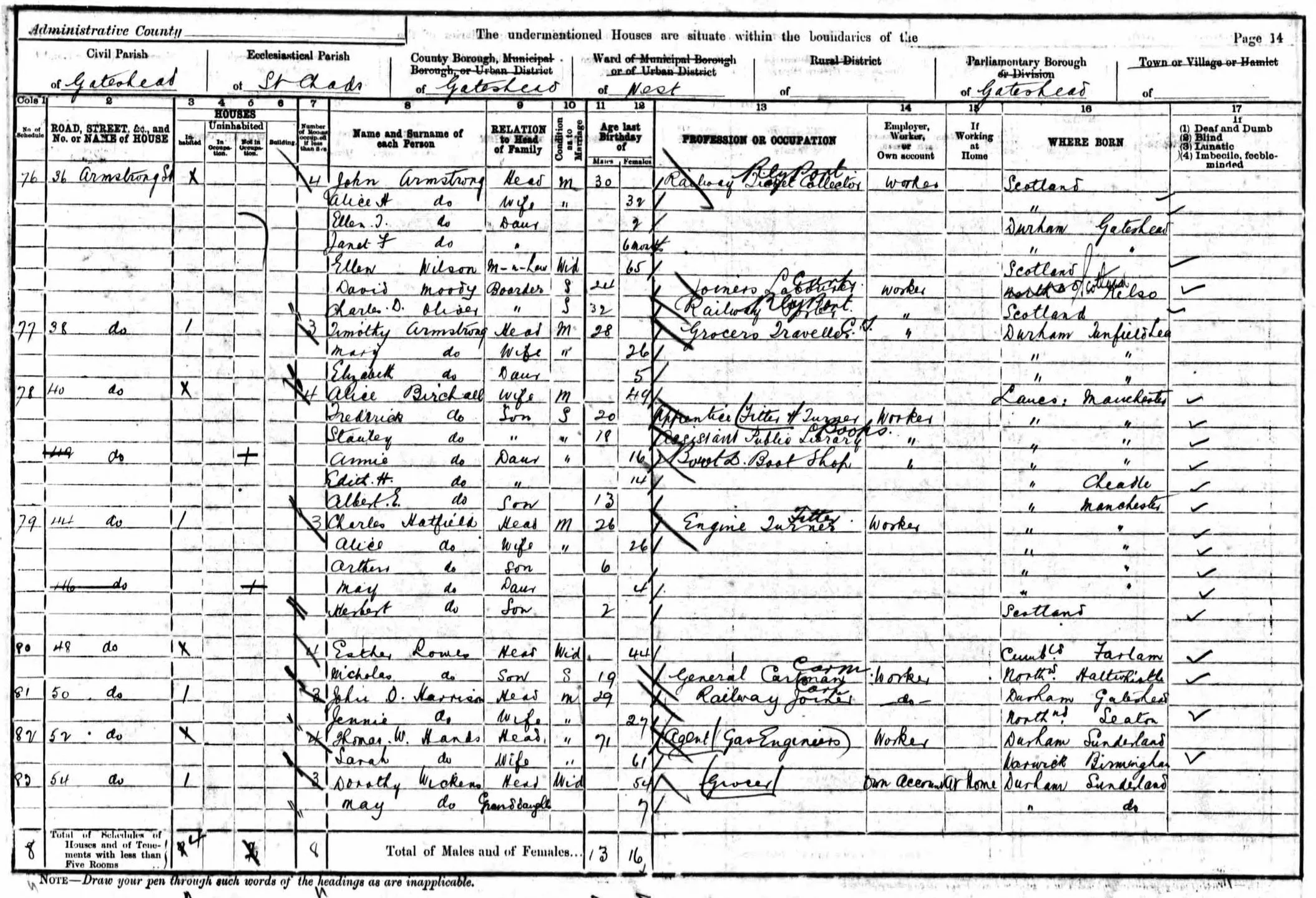

By 1901 the family had relocated to 40 Armstrong Street in Gateshead [13]. Frederick’s father was an electrical engineer and his skills were undoubtedly in need as industries looked to harness the power of electricity for the masses. It’s likely the family moved to remain close to Frederick (Senior) who was boarding in Durham and working at Shotton Colliery at the time [14].

1901 census [13]

Urbanisation spread relentlessly in Gateshead in the late 19th and early 20th century as the need for housing for workers in the factories increased. The Bensham area rapidly developed with Victorian terrace housing and Tyneside flats. By 1898 the North Eastern Railway had cut through, parallel to Saltwell Lane, taking trains north to Newcastle and beyond. The Gateshead Union Workhouse had also opened a new site just beyond the railway line, accessible via an underpass at the end of Armstrong Street.

Despite the large-scale urban development, the family benefitted from close proximity to Saltwell Park, known as “The People’s Park”. As one of the most beautiful public parks in the North East, Saltwell Park consisted of bowling greens, pavilions, an aviary, flower gardens, a maze, and a large lake supporting a variety of wildlife including wildfowl and resident birds. Many a visitor would have hired a rowing boat to cruise amongst the swans. Today the park remains a quiet oasis, attractively and beautifully laid out with lawns and flower beds close to the Dene with a small but pleasant waterfall splashing playfully down towards its southern boundary. The centrepiece of the park is the wonderful gothic mansion, Saltwell Towers [15]. Access to the extensive gardens and luscious green outdoor space would have been quite a contrast to the dank and squalid slums of Manchester and the family probably spent a significant amount of time visiting the grounds.

Map of Gateshead published in 1921 [16]. Armstrong Street is marked with a red box.

Postcard image of Saltwell Park in the early 20th century [17]

Frederick pursued a skilled trade, like his father, and undertook apprenticeship training as a fitter and turner. Typically lasting seven years, an apprenticeship was often the only way of self-advancement. Most engineering-focused apprentices entered the trade at 14 years old [18], so in 1901 Frederick may have been nearing completion of his training and contemplating his future.

Frederick Tinsley Birchall’s Royal Navy Service Record [19]

By 1903, the First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir John Fisher, had become increasingly concerned about the perceived threat posed by the Imperial German Navy. He immediately launched a programme which would be able to train engineers and artificers in the latest technology. Within two years, training centres were established at Chatham, Plymouth, and Portsmouth (Gosport). A recruitment brochure from the time highlighted the benefits of naval service [20], describing:

“Service in the Royal Navy offers great attractions to well-behaved men and boys who may wish, whilst seeing the world under pleasant conditions, to have a chance of distinguishing themselves by zeal and gallantry; it also provided continuous employment at a good rate of pay up to the age of 50, and to that of 55 in certain ranks and ratings, free rations, medical attendance and hospital treatment, allowance towards outfit, leave of absence without loss of pay, extra pay for special services, service in the Coast Guard, life pensions at expiration of service, and employment in Civil Service after being pensioned. There is no other service which offers such advantages as the Royal Navy, promotion being exceptionally rapid in the case of well-conducted, intelligent men who are determined to get on.”

Page from a Royal Navy Recruitment Brochure [20]

The role of an Engine Room Artificer was particularly attractive with an entry salary of 38s 6d per week, more than double an Armourer, a Sick Berth Attendant, or Stoker. Frederick was certainly suitably qualified and on August 6th 1903, at the age of 22, he joined the Royal Navy as a Fitter and Turner, signing on for 12 years [19] .

Frederick’s service records indicate he stood at approximately 5ft 6in, had light brown hair, had blue grey eyes, a fair complexion and possessed a very good character. A fit young man, Frederick completed his basic training and on October 1st 1903 joined the Firequeen II where he would continue learning naval customs, regulations and general seamanship. After successfully finishing his initial training, Frederick joins a series of ships and naval shore establishments in Portsmouth. Following their entry-level training, engineering artificers received in-depth and specialised education in mechanical engineering and naval technology. This training aimed to equip them with the necessary knowledge and skills to work on a wide range of machinery found on naval vessels, including engines, boilers, propulsion systems, and auxiliary machinery.

While Frederick was stationed in Portsmouth, a young Edith Henderson waited patiently in Gateshead. Edith, a local girl, lived with her family on Rodsley Avenue [21], which was just a short fifteen-minute walk from Armstrong Street and conveniently located only a block or so away from Saltwell Park. It’s quite possible that they crossed paths in the ornamental gardens or near the lake on a summer’s day. A little over a year after Frederick’s enlistment, Frederick and Edith married in their parish church, St. Chad’s. Stanley, Frederick’s brother is one of the witnesses and likely the best man.

Marriage Certificate for Frederick Tinsley Birchall and Edith Henderson [22]

In February 1905 Frederick is promoted to an Engine Room Artificer Class 4th Class and is quickly assigned to the HMS Cressy.

Photo postcard of HMS Cressy [23]

Powered by two 4-cylinder triple-expansion steam engines, the armoured cruiser had a maximum speed of 21 knots. The vessel had recently returned from China after three years’ commission and was due to join the Portsmouth Reserve Fleet [24]. Soon after Frederick had joined the ship’s company in May, the vessel underwent repairs [25]. It remains uncertain whether HMS Cressy left the port during the entirety of Frederick’s assignment, which was probably positive news for the young husband. Edith had become pregnant shortly after getting married and their first child, Frederick Hyde Birchall was born on August 13th, 1905.

From November 1905, Frederick was reassigned to HMS Duncan. The battleship had arrived back in Portsmouth for a refit [26] after being damaged following a collision with HMS Albion at Lerwick a month or so before [27]. The ship suffered hull damage including a hole below the waterline, rudder damage and the loss of her sternwalk.

During the spring of 1906, Frederick would likely have been onboard when the ship was dispatched from Barry, Wales, to assist in the unsuccessful salvage operation of HMS Montagu off Lundy Island in the Bristol Channel [28]. The Montagu had run aground at Shutter Point in thick fog [29]. While attempting to raise the Montagu, the Duncan struck rocks. The pierced hull led to flooding in an aft compartment [30].

HMS Montagu aground off Lundy Island in 1906 [31]

In August, Frederick was promoted again. This time to Engine Room Artificer Third Class, a rank equal to a Chief Petty Officer [32] and a very well paid role for the time.

Early the next year, HMS Duncan was transferred from the Channel Fleet to the Atlantic Fleet. The Atlantic Fleet was permanently based at Gibraltar to reinforce either the Channel or Mediterranean Fleet [33], and tasked to cruise to and from the base at Berehaven, Ireland. This would likely have been Frederick’s first experience leaving UK waters. The Barbary Macaques, distinctive Mediterranean-influenced architecture, Moorish fortifications, subtropical climate and the prominent limestone formation on the southern tip of the Iberian Peninsula would have made quite an impression on Lancashire-born Frederick.

Postcard of Commercial Square in Gibraltar c.1900 [34]

In the summer of 1907, Frederick and Edith’s second child was born, a daughter called Lilian Dorothy. Given Fredrick’s posting, it is unlikely he was present for the birth.

Frederick’s last significant journey as a member of the Duncan crew took place in July 1908, during the Quebec Tercentenary celebrations in Canada. Accompanied by the advanced British squadron, HMS Duncan steamed up the St. Lawrence River and moored beneath the Citadel at sunset [35]. The grand spectacle included illuminations and fireworks by the combined fleets in the harbour and saw the attendance of foreign dignitaries, among them the Prince of Wales (later King George V) [36].

Fireworks at the 1908 Quebec Tercentenary [37]

Frederick was shore-based in Portsmouth upon his return, undoubtedly to the delight of his young family. For a few weeks he was based at the Artificer Training Establishment, HMS Fisgard. A number of Victorian hulks (Audacious, Invincible, Hindostan and Sultan) moored at Hardway in Gosport were repurposed and served as the shore training establishment [38].

HMS Fisgard at Gosport [38]

Before the year was out, Frederick was reassigned to the torpedo depot ship, HMS Hecla. A re-fitted ex-British Empire merchant ship, the Hecla served with the Home Fleet. Between December 1908 and April 1909 the Hecla carried out various exercises around the Solent area [39,40] before sailing to Campbeltown [41] via Pembroke Docks [42] and Milford Haven. The Hecla was tasked with torpedo practice in the Kilbrannan Sound and Firth of Clyde, which aggravated local Argyllshire fishermen who saw the activity as being “detrimental to their interests and injurious to the fishing [41] ”. From this point, Frederick would spend much of his serving career in the waters of Scotland.

In late May, an incident occurred involving a crew member. A marine fell overboard and drowned in the icy Scottish waters while returning to the ship [43]. This incident served as a poignant reminder to Frederick and his fellow crew mates about the inherent dangers of serving in the Navy.

Over the subsequent months, the Hecla made a number of trips between Portsmouth and Scotland (Campbeltown, Oban, Rothesay), conducting manoeuvres and drills at sea. The mundane rhythm of naval life at sea only interspersed with occasional runs ashore.

After almost 18 months service on HMS Hecla, Frederick was redeployed on the HMS Blenheim, a depot ship for the First Destroyer Flotilla [44]. While Frederick’s time on the Blenheim was short, it was during this period he received a promotion to Engineer Room Artificer Second Class.

Frederick’s service record indicate time served aboard HMS Blake but at the time of the 1911 Census he was aboard the Torpedo Boat Destroyer, HMS Hope, which was moored off Portland [45]. He is one of only two Engine Room Artificers (E.R.A) working under Chief E.R.A Fred William McQuire.

1911 Census [45]

To mark King George V’s coronation, the Review of the Fleet took place on June 24th, 1911. More than 165 decorated warships positioned themselves between Portsmouth and the Isle of Wight through which the royal party steamed aboard the royal yacht. The Review was reportedly a magnificent success. Portsmouth was described as “bubbling over with enthusiasm for the Navy” and “hundreds of thousands of spectators who had come from far and near” lined Southsea Beach, Stokes Bay and the shores of the Isle of Wight. It is quite probable that Frederick participated in the Review. Although he likely missed much of the festivities while working below decks, he would have heard the thunderous 3000 gun salute [46] .

The 1911 Coronation Fleet Review [47]

When war broke out in July 1914, Frederick was serving on the newly commissioned cruiser, HMS Birmingham, which had joined the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron of the Grand Fleet earlier that year. Within days, Frederick and his crew mates found themselves on the frontline. On August 9, 1914, the Birmingham sighted a German U-boat whose engines had failed, forcing it to lie stopped on the surface amid heavy fog off Fair Isle, in Shetland. The crew of Birmingham could hear hammering from inside the boat as the Germans attempted repairs, and so they fired. After sweeping away the periscope and conning tower of U-15 with a salvo of six shots from Birmingham’s guns, the U-boat initiated a dive. With a turn of the helm, the Birmingham was brought around with her bows pointing straight at the disabled submarine. Captain Arthur Duff ordered the cruiser’s engines to be set at full speed. Then, dashing forward at 25 miles per hour, the 5,400-ton cruiser collided with U-15, which rolled over and sank to the bottom of the sea with all hands – the first U-boat loss to an enemy warship [48].

The HMS Birmingham also participated in the Battle of Heligoland Bight, the first major naval action of the war. On August 28th, 1914, shortly after daylight, the British Royal Navy, under the command of Vice-Admiral David Beatty, engaged German patrols off the north-west German coast resulting in the sinking of three German light cruisers and a destroyer, along with damage to three light cruisers. An eye witness described the fight [49]:

“It was a terrible sight. Shell after shell was blowing her to pieces; she was enveloped in a dense cloud of smoke and red tongues of flame were licking out the hull, and yet one or two men could be seen standing on her deck. How any man came out of that ship alive absolutely defeats me, and everyone else for that matter. Soon she was merely a blackened hull, very nearly under water, and it was obvious she had sailed her last voyage.”

Ultimately, the Battle of Heligoland Bight was a victory for the British, showcasing the effectiveness of their naval forces early in the war. The confrontation established the North Sea as a crucial theatre for naval operations. However, Frederick may not have realised that much worse was to come.

Before the year was out the German fleet attacked the East Coast towns of Hartlepool, Whitby and Scarborough [50] in an attempt to lure the British Grand Fleet out into the North Sea. Yet it was a further month before a significant naval engagement took place when Admiral Franz Ritter von Hipper targeted the British Fishing Fleet. British naval intelligence cryptographers had intercepted and decoded German wireless transmissions, thereby gaining advance knowledge that the German raiding squadron was en route to the rich fishing ground, Dogger Bank [51]. Naval forces were sent to intercept the German squadron, including HMS Birmingham as part of the 1st Light Cruiser Squadron [52].

On the morning of January 24th, 1915, the British ships steamed toward Hipper’s battlecruisers engaging the German forces in a fierce long-range battle. The German battlecruisers, including SMS Seydlitz, SMS Derfflinger, and SMS Moltke, put up a determined defence but the British ships, with their superior firepower and armour, initially had the advantage, pounding and sinking the SMS Blücher leading to the deaths of more than 700 men. However, a critical moment came when the British flagship, HMS Lion, was hit and temporarily disabled, causing confusion in the British line. Taking advantage, the German force made a tactical withdrawal putting enough distance between themselves and the British vessels to avoid probable annihilation and ensure a successful escape [53].

By early 1916, Frederick, now a Chief Engineer Room Artificer Second Class [19], had been assigned to the HMS Onslaught, an M-class Destroyer which formed part of the 12th Destroyer Flotilla of the Grand Fleet [54]. Based at Scapa Flow in the Orkney Islands, the crew spent much of their time cleaning and painting the ship, stripping guns, testing torpedos and participating in battle practice [55]. These activities probably became increasingly routine and mundane and occasional runs ashore would have provided a welcome break.

The Onslaught was out at sea on patrol for much of March, sailing between the Pentland Skerries, Scapa Flow, Swona and South Walls [56].

Map of the Orkney Islands, off the north coast of Scotland. HMS Onslaught patrol locations are shown in blue.

Strong winds and thick fog are common in the Orkneys. “No other region in Great Britain can compare with it for the violence and frequency of its winds” said Magnus Spence [57], a local school master who recorded the weather six times a day during World War One. In the dark half of the year, the average wind speed increases to around force 6, often force 7 or 8. More extreme gales, where the windspeeds are over 90 mph, occur relatively frequently, so it is unsurprising that the ship lost 3 hoses and 2 life buoys overboard in heavy seas [56] . Although Frederick would have adapted to life at sea, he and his fellow sailors may have encountered the unpleasant effects of seasickness amidst the rough seas.

Early in the evening of May 30th, 1916, the British Admiralty ordered Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and Vice Admiral Sir David Beatty to sea after receiving intelligence that the German High Seas Fleet would be put to sea the following morning. That evening the British Grand Fleet, under Admiral Jellicoe’s command, set sail from Scapa Flow and Cromarty. Vice Admiral Beatty’s Battle Cruiser Fleet and the 5th Battle Squadron left shortly after from their base at Rosyth further south in preparation for a 2 pm rendezvous the following day [58]. An account by Petty Officer Albert William Garland Symonds of the HMS Southampton suggests few knew the object of the operation. Consequently, Frederick and his fellow sailors would have had little inkling of the impending terror they were to face as the largest sea battle of the First World War commenced.

Map showing the movements of the British Grand Fleet and the German High Seas Fleet before the Battle of Jutland [60]

At 2.20 pm smoke from the enemy fleet was sighted by HMS Galatea, a light cruiser in Beatty’s fleet. Minutes later she fired the first shot of the Battle of Jutland. Jellicoe’s ships, along with HMS Onslaught, were still miles north of Beatty’s position.

Shortly before 4 pm, both sides commenced firing. The flagship of Admiral Hipper, SMS Lützow, initiated the exchange, with Admiral Beatty’s flagship, HMS Lion, responding moments later. Within minutes, a shell from the Lützow struck HMS Lion’s ‘Q’ turret, causing devastating damage. Minutes later, HMS Indefatigable explodes and sinks after being hit by SMS Von der Tann resulting in the tragic loss of over 1,000 lives. At 4.26pm, HMS Queen Mary receives a direct hit and is blown in half after its magazine explodes. Over 1,200 crewmen are killed. In a fierce confrontation, British and German destroyers engage each other, striving to launch torpedoes at the larger ships of the opposing fleet. During the clash, SMS Seydlitz sustains damage, and multiple German destroyers are lost. On the British side, two destroyers, HMS Nomad and HMS Nestor, are among the casualties of the intense exchange [61].

Just before 6pm, Jellicoe makes visual contact with Beatty’s battlecruisers. Hipper receives word that British dreadnoughts have been sighted to the east. Emerging from dense mist, the German battleships are met with the imposing sight of the Grand Fleet. Jellicoe orders the Grand Fleet to deploy in preparation for engaging with enemy forces.

HMS Invincible sustains a critical hit from SMS Derfflingerand. Invincible explodes, breaking in half. Over 1,000 members of the crew are killed, including Rear Admiral Hood. In response, British forces fire at a number of German vessels causing catastrophic damage. Outnumbered and fearing destruction, the German High Seas Fleet attempt to take advantage of the poor visibility to sail away from the Grand Fleet.

At 7.45 pm a division of the Twelfth Flotilla, including the Onslaught, proceeded to attack and sink an enemy destroyer before the German fleet altered course south, towards the safety of home waters. With darkness setting in, Jellicoe rejects a night action, favouring sailing south to renew the engagement at daylight.

In the early hours of June 1st, the Twelfth Flotilla sighted an enemy battle squadron. Just after 2 am the Onslaught received a signal from the Faulknor to attack the enemy [62]. When the Flotilla was heading for the enemy on a convergent and opposite course the order was passed to tubes: “Fire when your sights are on”. A torpedo launched by the Onslaught found its mark, striking the SMS Pommern. The impact likely triggered a catastrophic chain of events, as her 17cm ammunition magazines exploded and the ship was racked with several violent explosions in rapid succession. A colossal secondary blast ejected flames over 400 ft [58] tearing the SMS Pommern apart, splitting it in two. Debris rained down in the vicinity, with sizeable fragments, including sections of the turret roof and upper deck, plummeting into the water perilously close to the SMS Deutschland. Tragically, there were no survivors from the SMS Pommern’s crew of 839 [63].

Plan drawn by John Fawkes showing the British 12th Destroyer Flotilla’s attack at dawn 1st June 1916 on the German Battle Line during the Battle of Jutland [64]

What happened next is described by 19-year Sub Lieutenant Harry Kemmis, as the most senior remaining officer on HMS Onslaught. The Onslaught turned to starboard, meanwhile the enemy fired and a “shell burst against the port side of the chart house and fore bridge, igniting a box of cordite, causing a fire in the chart house, completely wrecking the fore bridge and destroying nearly all navigational instruments. At the time there were on Fore Bridge:- The Captain, First Lieutenant, Torpedo Coxswain, 2 Quartermasters and both Signalmen and the Gunner on his way up the bridge ladder. I had just been sent down to tell the Engine Room to make black smoke, in order to screen our movements…I went back to the bridge and finding everything wrecked, Captain mortally wounded and the First Lieutenant killed, I assumed command and gave orders for the after steering position to be connected, which was done very smartly [62]”.

Depleted of torpedoes, with a disabled gun, all key personnel among the casualties, and critical damage to instrumentation, the Onslaught requested permission to return to the harbour at the Firth of Forth. Upon reaching May Island, Frederick and the crew were escorted to the Forth Bridge ready to take the dead and injured ashore.

As the smoke cleared and the waves calmed, the toll of the battle became painfully evident. Fourteen British ships lay at the bottom of the sea, their once-proud hulls now silent graves for brave sailors. Another thirty bore the scars of battle, battered and wounded but still afloat. The Germans, too, felt the sting of war, with eleven of their vessels lost to the depths and thirty more bearing the scars of conflict.

The human cost was staggering. Nearly seven thousand British souls perished in the ferocity of the conflict, while over three thousand Germans met their end amidst the chaos of battle. Frederick would undoubtedly have felt immense gratitude or overwhelming guilt at his survival, recognising the stark contrast between his own fortune and the devastating loss endured by countless others.

Days later Sub Lieutenant Kemmis submits his report acknowledging the actions of the crew:

“The behaviour of the Ship’s Company during the whole action and afterwards deserves the highest praise…To the efficiency and a coolness of the Engine Room Staff is due in large measure the escape of the ship after being hit [65]”

Beatty echoes Kemmis’ statements in a telegram:

“As usual, the Engine Room Departments of all the ships displayed the highest qualities of technical skill, discipline and endurance. High speed is a primary factor in the tactics of the squadrons under my command, and the Engine Room Departments never fail [66].””

Following the battle, neither side could claim a decisive victory. The waters of the North Sea remained contested. Despite the losses, the British Grand Fleet stood firm, maintaining its grip on the vital sea lanes that sustained the Allied war effort all the while continuing the German blockade that steadily eroded the enemy’s strength and resolve.

For the crew of the Onslaught, work immediately began on clearing wreckage and undertaking repairs at Rosyth before proceeding to dry docks at Leith [67]. By July, the Onslaught was deemed seaworthy, and Frederick, along with the crew, had set sail for Scapa Flow. They were preparing for sea patrols to scout for enemy submarines in the waters between Banff, Kinard Head, Invergordon, and the Pentland Skerries [68].

A month later, the Onslaught and Marvel were tasked with escorting the light cruiser, Royalist, to rendezvous with the Grand Fleet. Just before dark the convoy was attacked by the German submarine UB-27. Searchlights frantically attempted to locate the enemy. A trail of bubbles from a speeding torpedo revealed imminent danger, targeting the Onslaught. Fortunately, the torpedo missed its mark and the attack ended abruptly [69]. The constant threat of enemy action, so soon after Jutland, must have been stressful for Frederick and his fellow sailors.

Throughout September, Frederick and his fellow crew mates settled into a familiar routine while at sea in the chilly Scottish waters, which included ship maintenance, physical exercise, drills and battle practice, patrols, oil refuelling, prayers, with occasional visits to shore [70]. It was during this month, that Frederick was honoured with the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal [71] for his role in safeguarding the HMS Onslaught from certain destruction at Jutland. The Conspicuous Gallantry Medal is bestowed upon non-commissioned personnel who display gallantry in action, and Frederick was one of only 15 recipients following the battle and one of 108 recipients during World War One.

List of Conspicuous Gallantry Medal recipients following action at the Battle of Jutland [71]

The remainder of the year was relatively quiet with the Onslaught making patrols around Swona, Pentland Skerries, Cromarty, Gutter Sound, and the North Sea70. Frederick found himself celebrating Christmas and New Year many miles from home, likely receiving a small package of gifts and festive cards from his loved ones. To keep up morale and to pass the time, the crew may have held theatrical shows, pantomimes and sung carols like those on HMS Iron Duke.

Postcard from 1916 depicting the crew of HMS Iron Duke celebrating Christmas [72]

Festivities were brief. The new year opened with exercises at sea, and in the subsequent days, the Onslaught resumed sea patrols. During that first month, the crew sailed beyond Scottish waters, making trips to Liverpool and Belfast [73]. By February, the Onslaught had returned to the Orkney Islands.

Frederick may have been woken abruptly in the early hours of March 13th. At 02:04 am, the HMS Obedient and HMS Onslaught collided on the way to Stornoway. A 13-ton shackle, brake lever, and two gun covers were among the items lost. Significant damage to the ship was likely, as the Onslaught was in Glasgow’s dry docks for repairs within days [74]. Drama continued when fire broke out onboard on April 4th. The fire party were immediately deployed and it appears the fire was swiftly extinguished [74].

With repairs and restocking complete, Frederick and the crew aboard the Onslaught departed for Greenock on May 2nd, and patrols resumed [75]. Frederick must have been grateful to see calmer seas and the weather improving.

In early June, HMS Onslaught embarked on a new mission, departing from the Shetland archipelago and charting a course to the rocky island of Holmengrå off the western coast of Norway. Throughout the subsequent months, the crew sailed repeatedly between Lerwick, Holmengrå, Batalden, Marsteinen and the Fjords near Bergen, examining fishing vessels and patrolling for the formidable U-boats that prowled the North Sea [75,76].

By October, the ship had returned to Scapa Flow and on October 29th at 21:11 pm, the Onslaught was grounded at Gutter Sound [77]. Despite clearing ground swiftly, Able Seaman Wilfred Jack Henry Spencer fell overboard and was accidentally drowned [78].

Fortune did not favour the Onslaught and her crew. In November, the ship was struck on the port side by the trawler ‘Aracari,’ which damaged the engine room as the ship passed through the Fidra Gap in the Firth of Forth. Moments later, the Onslaught collided with the Obedient in her port quarter. The vessel was clearly compromised and, in the early hours, required a salvage tug to tow her to Victoria Basin. The following day, Frederick found himself at Alexandra Docks with the ship undergoing repairs [79].

Much like the two years before, Frederick began the year undertaking exercises at sea, patrolling the waters around Scotland and performing the usual cleaning and maintenance duties aboard the HMS Onslaught. The weather was often rough, with strong gale-force winds on occasion [80]. Undoubtedly, the high waves, pitching of the ship and airborne sea spray made the crew’s working conditions difficult and unpleasant.

On May 15th, 1918, Frederick’s second daughter and third child, Edith, was born 500 miles away in Portsmouth. Meanwhile, Frederick was at sea, patrolling the Firth area, engaged in an uneventful day making and mending [81]. He likely received the joyful news a day or two later by telegram, marking a bittersweet moment amid his duties.

A month later, the crew of the Onslaught navigated their way through the Mull of Cantyre (Kintyre) and up the River Clyde, passing the scenic hilly moorlands of the Kintyre peninsula. Once at Govan docks the ship was de-ammunitioned [81] and Frederick found himself transferred to the depot ship, HMS Woolwich [19] . He was likely at Rosyth when the war ended on November 11th 1918. It is possible that he participated in escorting the 70 German ships into the sheltered estuary north of Edinburgh, alongside numerous Allied vessels and aircraft, adding an intriguing dimension to his wartime experience. This moment not only signifies the end of hostilities but also highlights the critical role he, and others like him, played in the naval operations of that time.

The Front Page of the Daily News reporting the German Navy Surrender [82]

Frederick’s naval record [19] indicates that he returned to the Onslaught on April 1, 1919, when the destroyer had already been relegated to reserve service in Portsmouth [83]. The rigours of wartime service, compounded by the ungalvanised hull and the demands for high-speed operations in rough seas, had taken a toll on the ship, which was ready for retirement. During the period from April to mid-July, Frederick and his fellow crew members were stationed in Portsmouth [84,85] . This must have been a significant relief for him and his family, providing them with much-needed quality time together after the stresses of active duty. The opportunity to reconnect and recuperate would have been invaluable for both Frederick and his loved ones.

Perhaps looking forward to a period of extended peace, Frederick may have been surprised when he was deployed to the Baltics during his service on HMS Shakespeare. The situation in Latvia and Estonia in the aftermath of World War I was chaotic. The Russian Empire had collapsed, and the Bolshevik Red Army, along with pro-independence and pro-German forces, were fighting across the region. In response, the British intervened, sending naval forces shortly after the Armistice. Thankfully, when the Shakespeare returned to the Baltic in July 1920, hostilities between Britain and the Bolsheviks had ceased [86]. No doubt Frederick would have been relieved.

From August through November of that year, Frederick found himself in familiar territory, participating in manoeuvres, tactical attack exercises, torpedo practice, and station-keeping in Scottish waters [87,88,89] . However, by mid-December, the crew of the Shakespeare had returned to Portsmouth, and Frederick was with his family for the festive season, likely for the first time since before the war had began.

Frederick’s service record reflects consistently exemplary performance throughout his naval career, making his promotion to Chief Engine Room Artificer First Class in early 1922 unsurprising. With this promotion came a pay increase to 12 shillings and 6 pence per day, supplemented by additional allowances for extra duty, good conduct, and specific ERA certifications [90]. This recognition not only underscored his skills and dedication but also enhanced his financial stability during his service.

The remainder of Frederick’s naval career involved assignments at Fisgard, the training centre for naval engineers and artificers, and aboard HMS Rocket, a vessel assigned to the torpedo school in Portsmouth [91]. With over two decades of extensive experience, Frederick was likely entrusted with the training of new recruits.

On August 13, 1925, at the age of 44, Frederick was discharged from the Royal Navy, concluding a long and often tumultuous career at sea [19] . Records of his later life are scarce, making it difficult to determine his exact activities, but it is known that he spent some time working as a Marine Engineer overseas. In July 1926, Frederick stepped off the SS Oroya in Liverpool, having sailed from Cristóbal, a bustling port town on the Atlantic side of the Panama Canal [92]. Once a quiet outpost of the Colón District, Cristóbal had been transformed as civilian traffic increased year on year [93] traversing the Panama waterway. As ships surged through this critical artery of global trade, so did the demand for skilled marine engineers like Frederick, men who were willing to journey across the seas to keep the engines of commerce running.

Frederick’s journey home spanned 5,500 nautical miles across the Atlantic [94], starting in the sweltering, tropical climates of Panama and Havana, Cuba. From there, he sailed into cooler waters, stopping at Vigo, A Coruña, and Santander in Spain, before reaching La Rochelle, France, and finally arriving in Liverpool [95].

Map showing Frederick’s journey in 1926 [94,95]

A photograph from that summer captures a peaceful moment: Frederick, safely back home, relaxing in the garden with his daughters, Lilian Dorothy and Edith Elsie. The images that follow over the years paint a picture of a man devoted to family life, cherishing simple joys after years spent at sea. These snapshots of family gatherings and quiet afternoons hint that Frederick’s journey to Panama may have been his final adventure, marking the end of his travels and the beginning of a chapter filled with memories made closer to home.

A photograph of Fredrick Tinsley Birchall and his daughters. Taken in the summer of 1926.

From simple beginnings, Frederick had worked hard, successfully improving his social status significantly. By 1929, he had moved his family into a new semi-detached home on the Baffins Road development [96,97] – a far cry from the crowded slum housing of his childhood. Frederick never forgot his roots and named his home “Saltwell” after the beautiful park in Gateshead.

Opening of the new Baffins Road, Copnor, Portsmouth [98]

With the threat of war looming, the UK Government introduced the National Service (Armed Forces) Bill, which received Royal Assent on 3rd September 1939, just hours after the Prime Minister declared a state of war with Nazi Germany. This Act superseded the Military Training Act of 1939 and required male subjects between the ages of 18 and 41 years to be eligible for conscription. Frederick, though likely eager to serve his country, was 58 years old and in a skilled profession, making him ineligible for active service.

At the time of the 1939 Register, Frederick was living with his wife, daughters and young granddaughter, Brenda. This snapshot of the civilian population, taken just after the outbreak of Second World War, records Frederick working as an Armament Fitter in the Torpedo Depot at Portsmouth Dockyard. While not on the frontlines, Frederick was still making a vital contribution to the war effort, applying his engineering skills in support of the military.

1939 Register [99]

German bombing raids began in the summer of 1940, with Portsmouth—a key hub for the Royal Navy and numerous military and industrial installations—becoming a prime target. Despite the Luftwaffe’s relentless attacks throughout the war, which left much of the city in ruins, Baffins Road miraculously escaped unscathed. The nearest bombs fell on neighboring Kimbolton Road and Hayling Avenue [100].

Scant information is available to detail Frederick’s life in the post-war years. However, Frederick and Edith were certainly still living in Baffins Road at the time of their Golden Wedding Anniversary in 1954 [101].

By November 1963, Frederick had retired from his duties at the Dockyard. Now an elderly man, he must have been in considerable pain and discomfort, when he was admitted to St Mary’s Hospital for abdominal surgery (laparotomy). At the age of 82, this war hero and devoted family man finally succumbed to heart failure, complicated by advanced gall bladder cancer.

Death certificate for Frederick Tinsley Birchall [102]

References:

[1] England and Wales, Birth Registration Index, 1837-2008, index, Volume 8c Page 797, Frederick Tinsley Birchall

[2] Information available at http://pubs-of-manchester.blogspot.com/2013/05/dog-partridge-elton-street.html

[3] Douglas. I et al. Industry, environment and health through 200 years in Manchester. Ecological Economics, 41(2), 235-255. (2002).

[4] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881; Class: RG11; Piece: 3919; Folio: 64; Page: 52; GSU roll: 1341936

[5] Ordnance Survey. (1891). Manchester [Map]. 1:500. OS Town Plan. Available at https://maps.nls.uk/view/231274602

[6] Manchester Libraries. ‘Chorlton-on-Medlock, James Street, 1995’. 2011. Online image. Flickr. 28th August 2023. https://www.flickr.com/photos/manchesterarchiveplus/5984326772

[7] Manchester, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1915. St Matthew’s Church, Ardwick, Manchester. March 1st 1888. Birchall, Annie. https://www.Ancestry.com : accessed August 31st 2023.

[8] Ordnance Survey. (1891). Manchester [Map]. 1:500. OS Town Plan. Available at https://maps.nls.uk/view/231274605

[9] A Hundred Years of Road Passenger Transport in Manchester. Manchester Corporation Transport Department. Centenary of Municipal Government. Available at: https://rusholmearchive.org/_file/E6dZtHsHYS_180324.pdf

[10] Image provided by Ted Gray and taken from the Tramway Systems of the British Isles. Image available at http://www.tramwaybadgesandbuttons.com/page148/styled-79/page384/page384.html

[11] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1891; Class: RG12; Piece: 3166; Folio: 94; Page: 17; GSU roll: 6098276

[12] Poor Rate Assessments for Ardwick Township (1891). Greater Manchester Rate Books. Available on www.FindMyPast.com

[13] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901; Class: RG13; Piece: 4752; Folio: 156; Page: 14

[14] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901; Class: RG13; Piece: 4685; Folio: 49; Page: 19

[15] Information available at: https://www.gateshead.gov.uk/article/3958/Saltwell-Park

[16] Ordnance Survey. (1921). Gateshead [Map]. 1:10560. OS Town Plan. Available at: https://maps.nls.uk/view/102341470

[17] Image available at: https://pin.it/1kxN3UmCN

[18] Knox, W. (1980). British Apprenticeship, 1800-1914. Ph.D Thesis. University of Edinburgh. Available at: https://era.ed.ac.uk/bitstream/handle/1842/6838/236380.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

[19] The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Royal Navy Registers of Seamen’s Services; Class: ADM 188; Piece: 435

[20] Royal Navy Recruitment Brochure (1900). Available at: https://thefisgardassociation.org/images/nostalgia_docs/brochures/recruitment_brochure_1900.pdf

[21] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901; Class: RG13; Piece: 4754; Folio: 38; Page: 23

[22] ‘Frederick Tinsley Birchall’ (1904). Certified copy of marriage certificate for Frederick Tinsley Birchall, 29 March 2021. Application number 11604161/1. Gateshead Register Office.

[23] Image from Wikimedia Commons. Available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HMS_Cressy_real_photo_postcard.jpg

[24] Launch of a Scout. (1905, February 7th.) The Globe. Page 7.

[25] Dockyard Gossip. (1905, May 26th.) The Evening News. Page 2.

[26] Naval and Military. (1905, October 9th.) The Evening News. Page 5.

[27] The Ramming of H.M.S. Duncan. (1905, October 4th.) The Evening News. Page 4.

[28] Battleship Ashore at Lundy. (1906, May 31st.) The North Devon Journal. Page 8.

[29] Series of Naval Accidents. (1906, June 2nd). The Hampshire Telegraph. Page 4.

[30]Salvaging the Montagu. (1906, July 26th.) The Evening News. Page 5.

[31] National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Gibson’s of Scilly Shipwreck Collection. Image available at: https://images.rmg.co.uk/asset/47589/

[32] Information obtained from Royal Museums Greenwich at: https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-74600

[33] Information obtained from https://www.naval-history.net/xGW-RNOrganisation1900-14.htm

[34] Image taken from: https://www.reddit.com/r/vexillology/comments/wy26pu/i_collect_old_postcards_of_my_hometown_gibraltar/?utm_source=share&utm_medium=web3x&utm_name=web3xcss&utm_term=1&utm_content=share_button

[35] The Quebec Tercentenary. (1908. July 17th.) The Mail. Page 2.

[36] Reid, Mark “The Quebec Tercentenary, 1908: Canada’s First National Military Pageant.” Canadian Military History 8, 2 (1999).

[37] Display at the Tercentenary Fetes, Quebec, July 23rd, 1908. From a drawing by C.M. Padday. Image taken from Pyrotechnics: The History and Art of Firework Making (2021). Project Gutenberg.

[38] Information taken from Gosport Heritage Open Days website at https://www.gosportheritage.co.uk/hms-fisgard-gosport-1904-1932/

[39] The Fleet. (1909, February 20th.) The Army and Navy Gazette. Page 184

[40] The Fleet. (1909, February 27th.) The Army and Navy Gazette. Page 208.

[41] Torpedo Practice and Injury to Fishing. (1909, May 10th.) The Aberdeen Daily Journal. Page 5

[42] The Fleet. (1909, April 24th.) The Army and Navy Gazette. Page 399.

[43] The Fishing Industry. (1909, May 27th.) The Banffshire Advertiser. Page 8.

[44] Information available at http://www.dreadnoughtproject.org/tfs/index.php/H.M.S._Blenheim_(1890)

[45] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1911; Class: RG14; Piece: 12373; Schedule: 9999

[46] The King and his Fleet. (1911, June 24th.) The Evening News. Page 1.

[47] The Coronation of King George and Queen Mary: The Abbey Ceremonies; the Processions; and the Naval Review. (1911, June 27th.) Illustrated London News. Page 24.

[48] The German Defeat. (1914, August 14th.) Hampshire Telegraph. Page 7.

[49] Heligoland Fight. (1914, September 25th.) Hampshire Telegraph and Post. Page 10.

[50] Thick Fog. (1914, December 18th.) The Western Times. Page 7.

[51] Sir Alfred Ewing. (1935, January 8th.) The Yorkshire Post. Page 5.

[52] Naval Despatches. (1915, March 6th.) The Army and Navy Gazette. Page 194.

[53] Information taken from https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/the-battle-of-dogger-bank-january-1915/

[54] Supplement to the Monthly Navy List. (March, 1916.) Page 12.

[55] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53296

[56] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53297

[57] Information taken from https://www.orkneyjar.com/orkney/climate.htm

[58] Jellicoe, J. R. (1920). Battle of Jutland, 30th May to 1st June, 1916: Official Dispatches with Appendixes (Vol. 2). H.M. Stationery Office. (printed by Eyre and Spottiswoode).

[59] Excerpt from the Journal of Petty Officer Albert Symonds, available via the Royal Naval Writer’s Association: https://rnwa.co.uk/battle-of-jutland-31-may-1-june-1916/

[60] Image taken from https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205132687. © IWM (Q 71358)

[61] Details taken from https://www.iwm.org.uk/history/battle-of-jutland-timeline

[62] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Reports of Flag and Commanding Officers – Jutland, ADM 137/302, Page 569.

[63] Detail taken from https://www.kaisersbunker.com/pommern/karten/pommern.htm

[64] Image taken from https://rnwa.co.uk/battle-of-jutland-31-may-1-june-1916/

[65] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; Reports of Flag and Commanding Officers – Jutland, ADM 137/302, Page 570.

[66] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England; London Gazette, Official Dispatches, ADM 137/301, Page 141.

[67] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53298

[68] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53299

[69] Naval Staff Monographs (Historical). Vol. XVII. Naval Staff Training and Staff Duties Division. 1927. Page 98. Available at: https://seapower.navy.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/Naval-Staff-Monographs-Vol.XVII_opt.pdf

[70] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53300

[71] Recorded in Supplement to The London Gazette, issue 29752 (15th September 1916), pg 9085. Available at https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/29752/supplement/9085/data.pdf

[72] Postcard image taken from The Great War (1914-1918) Forum and supplied by community member Mike Meech. Available at https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/189512-hms-iron-duke-christmas-1916/.

[73] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53302

[74] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53303

[75] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53304

[76] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53305

[77] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53306

[78] Information taken from https://www.greatwarforum.org/topic/147000-hms-diligence/page/2/.

[79] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53307

[80] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53308

[81] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53310

[82] Germans Meet Beatty at Rosyth. (1918, November 16th.) Daily News. Page 1.

[83] “IV. Vessels in Reserve at Home Ports and Other Bases”, Supplement to The Monthly Navy List, p. 16, May 1919, – via National Library of Scotland

[84] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53313

[85] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/53314

[86] Information available at https://naval-encyclopedia.com/ww1/uk/shakespeare-class-destroyer-leaders.php

[87] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/59902

[88] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/59903

[89] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, Surrey, England, Admiralty, and Ministry of Defence, Navy Department: Ships’ Logs, ADM 53/59904

[90] Information extracted from https://sites.rootsweb.com/~pbtyc/LondonGazette/Pay_Rates_1920.html

[91] “III – Local Defence and Training Establishments, Patrol Flotillas, Etc”. The Navy List: 704. October 1919 – via National Library of Scotland.

[92] The National Archives of the UK; Kew, Surrey, England; Board of Trade: Commercial and Statistical Department and successors: Inwards Passenger Lists; Class: BT26; Piece: 813

[93] The Panama Canal Record. (1921). (Vol. 14). The Panama Canal Press.

[94] Estimated using Google Maps. Google. (n.d.). [Google Maps journey from Cristóbal to Liverpool]. Retrieved October 4, 2024, from https://bit.ly/3zNWUKC

[95] Route details for the SS Oroya journey in 1926 available at http://www.timetableimages.com/maritime/images/psn.htm

[96] Births, Marriages and Deaths. (1929, September 5th.) The Evening News. Page 8. Article confirms Birchall family are living in Baffins Road.

[97] New Baffins Road. (1929, March 16th.) The Evening News. Page 3.

[98] Image taken from https://bygone.co.uk/archive/opening-of-the-new-baffins-road.318/

[99] The National Archives of the UK (TNA); Kew, London, England; 1939 Register; Reference: RG 101/2283E

[100] Data shown on the Portsmouth Museum’s Bomb Map at https://portsmouthmuseum.co.uk/collections-stories/80th-anniversary-of-the-blitz/the-portsmouth-bomb-map/

[101] Births, Marriages, Deaths, etc. (1954, September 2nd.) The Evening News. Page 18.

[102] ’Frederick Tinsley Birchall’ (1963). Certified copy of death certificate for Frederick Tinsley Birchall, 27 November 1963. Application number 13560700/3. Portsmouth Register Office.